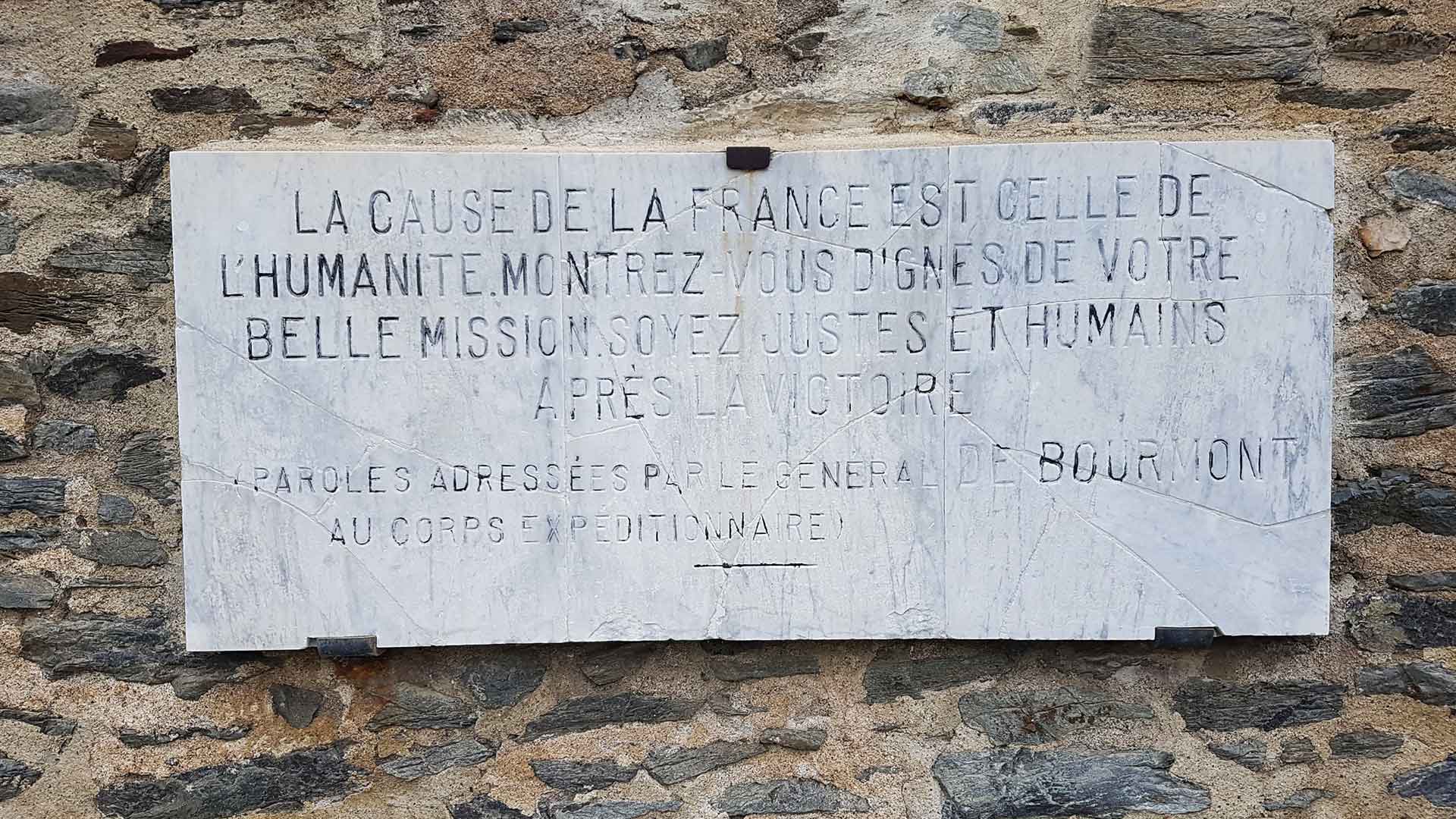

The Sidi-Brahim monument

The battle of Sidi Brahim, 22-25 September 1845, is a key lieu de mémoire in Algeria. The memory of this French defeat against Algerian resistance led by Emir Abdelkader has been mobilised in the service of both Algerian nationalism and European hegemony in Algeria. Heavy losses to the French 8th Batallion of the Chasseurs d'Orléans and the 2nd Hussards have been central to the mythologisation of the battle ever since, especially through the final words of Captain Louis Dutertre: «Camarades défendez-vous jusqu'à la mort !» (Comrades, defend yourselves to the death!).

In Oran’s Place d’Armes, a monument to the French martyrs of Sidi-Brahim was inaugurated in 1898, designed by Jules Dalou. Dalou’s monument consisted of an obelisk topped by the feminine incarnation of liberty, supported at the base by a statue of Marianne inscribing Dutertre’s final words on the obelisk.

In commemorating the French dead and defeated of Sidi-Brahim, like the First World War monuments of France and Algeria, the monument’s design seeks to commemorate the blood sacrifice made by French men in the conquest of Algeria, legitimising the French colonial project in a settler context.

Yet, as with all the colonial monuments we have explored so far, although constructed in limestone, marble, and concrete, these structures are fluid signifiers whose meanings develop over time. We can explore these evolutions through the changes to the physical structures, but also in ways they are represented culturally. Notably in Camus’s La Peste (1947), the monument is restaged in an imagined Oran besieged by plague. Instead of colonial splendour, it provides the dreary décor for an argument between Dr Rieux, the novel’s protagonist, and Rambert, the visiting journalist who finds himself trapped in plague-infested Oran. As Rambert pleads with the doctor to help him leave, Rieux reflects on the state of the statue:

‘Rieux approuva de la tête, il reçut un petit garçon qui se jetait dans ses jambes et le remit doucement sur ses pieds. Ils repartirent et arrivèrent sur la Place d’Armes. Les branches des ficus et des palmiers pendaient, immobiles, grises de poussière, autour d’une statue de la République, poudreuse et sale. Ils s’arrêtèrent sous le monument. Rieux frappa contre le sol, l’un après l’autre ses pieds couverts d’un enduit blanchâtres. […]

- Non, dit Rambert avec amertume, vous ne pouvez pas comprendre. Vous parlez le langage de la raison, vous êtes dans l’abstraction.

Le docteur leva ses yeux sur la République et dit qu’il ne savait pas s’il parlait le langage de la raison, mais il parlait le langage de l’évidence et ce n’était pas forcément la même chose.' (Camus 1947 [1962] pp.100-102)

‘Rieux nodded. A small boy had just run against his legs and fallen; he set him on his feet again. Walking on, they came to Place d’Armes. Grey with dust, the palms and fig-trees drooped despondently around the statue of the Republic, which too was coated with grime and dust. They stopped beside the statue. Rieux stamped his feet on the flagstones to shake of the coast of white dust that had gathered on them. […]

‘No,’ Rambert said bitterly, ‘you can’t understand. You’re using the language of reason, not of the heart; you live in a world of … of abstraction.’

The doctor glanced up at the statue of the Republic, then said he did not know if he was using the language of reason, but he knew he was using the language of the fact as everybody could see them – which wasn’t necessarily the same thing.’ (Camus 1947 [1960] pp.72-73)

For Debarati Sanyal, Camus’s choice to shroud the monument in ‘dust and anonymity’ is odd considering ‘his intimate knowledge of Oran’ and the monument’s significance to the city’s colonial topography and as a lieu de mémoire of colonial conquest. Instead, covered in dust and referred to solely as ‘la République’ the monument appears to have been washed of references to its colonial past.

Camus’s fictional Oran is shorn of any such palimpsestic texture. It remains a carefully constructed non– lieu de mémoire whose blank neutrality might appear simply to extend the universalizing reach of its allegory. Yet the omission of the monument, with its commemoration of the sacrifice of colonial troops in this central scene of The Plague is a telling choice that reveals something about the fate of Algeria’s pied-noir population. The Sidi-Brahim monument bore witness to the category of the victim-perpetrator or persécuté-persécuteur that defines the pied-noir’s historical position for Camus, who in the autobiographical The First Man sought to reimagine the itinerary of these European settlers as they fled persecution in 1848 and 1870 to occupy the lands of indigenous Algerians. In The Plague, the monument’s anonymity seems a harbinger of the settlement’s demise. Marianne’s irrelevance—indeed her displacement from Camus’s narrative frame—foreshadows the literal removal of the Republic (and of France) fifteen years later. (Sanyal 2015: 73)

From colonial eulogy in stone to Camus’s literary foreshadowing of the failure of settler colonialism in Algeria, the monument invites many different readings.

By staging French defeat at Sidi-Brahim, the monument is also significant as a lieu de mémoire for anti-colonial resistance. As the interwar year witnessed growing Algerian nationalism, Sidi-Brahim and Emir Abdelkader’s victory gained in symbolic power. Notably, the honorary President in exile of the Étoile Nord Africaine was Émir Khaled, Abdelakder’s grandson.

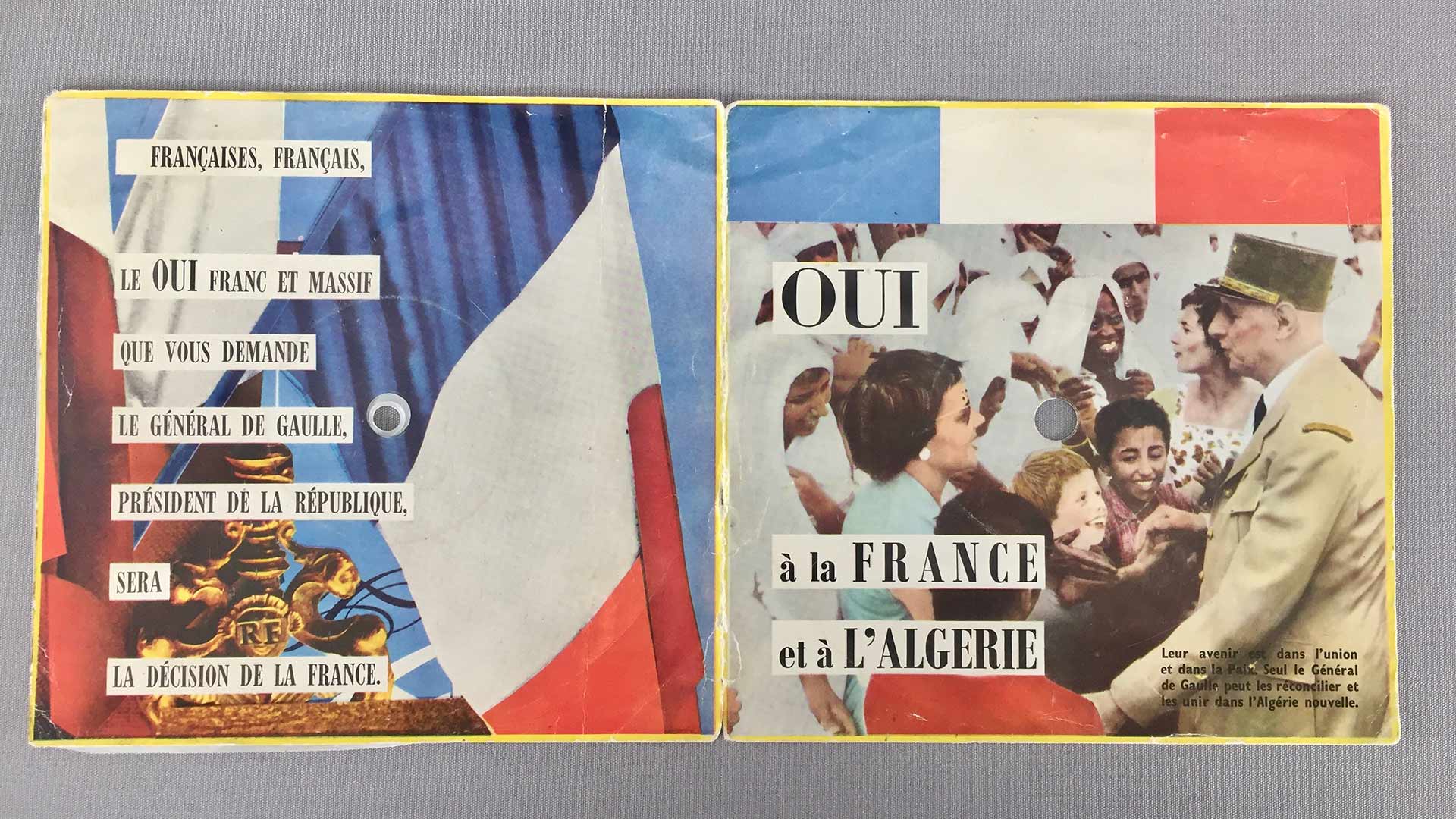

With independence in 1962, another layer sedimented in Oran’s urban palimpsest. The Sidi-Brahim monument was transformed into a celebration of Algerian victory in 1845 and as a monument to Emir Abdelkader but also, implicitly, the martyrs of the recent anti-colonial conflict with France. Beyond the history of French invasion in the 19th century, Adbelkader became the national hero par excellence for a country rebuilding itself after independence. The renaming of the square from Place d’Armes to Place du 1er Novembre reinforced the monument as a lieu de mémoire to 1954 as much as 1845.

While the obelisk and figure of victory have remained, the statue of Marianne at the base has been removed. Instead, four reliefs of Abelkader’s portrait and commemorative text in Arabic are displayed on each façade, reading “And there is no victory outside Allah’s providence, Allah the omnipotent, the wise.”

The removed statues of France were repatriated to the small town of Périssac, in Gironde, the birthplace of Capitaine Oscar de Géreaux, who died in the battle of Sidi-Brahim. After 1962, Colonels Henri Tourniaire and Péninou arranged for the statue to be re-inaugurated in the small village in 1966, with a new architectural structure that was designed by architect François Courrech.

Now, Camus’s ‘la République’ is enshrouded in a new layer of meaning in service of the memory of lost French Algeria. Residing far out in the French countryside, the kneeling figure of the Marianne appears sheltered and defended by the enveloping, protective wall that curves around her.