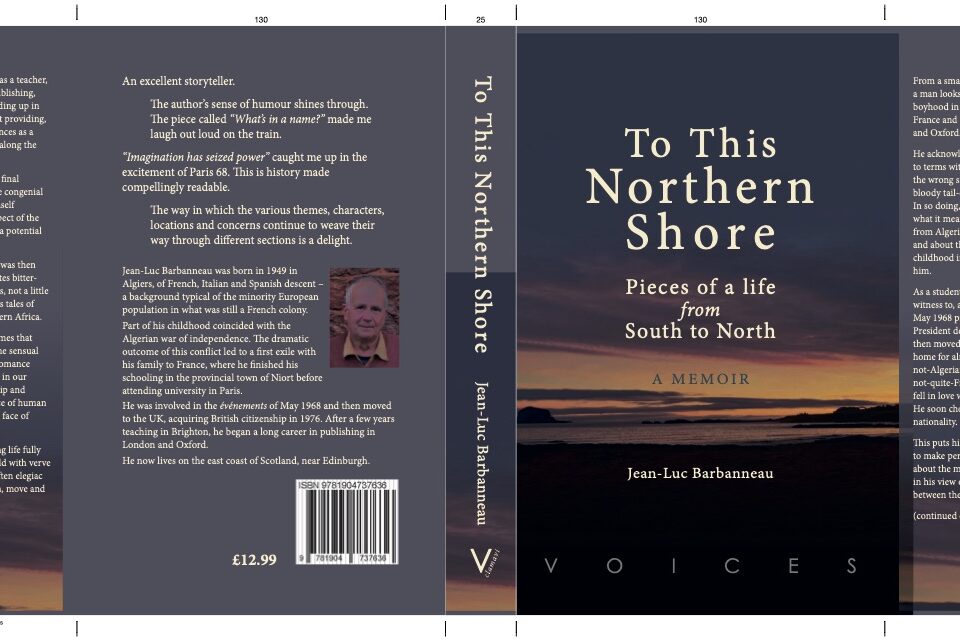

Plague, pilgrimage, and the pieds-noirs

For the vast majority of the settlers who left Algeria in 1962, the physical return to Algeria would be impossible for many decades. Now in France, how could they maintain immaterial connections to the homes and communities left behind? In the absence of physical sites of memory – left irrevocably behind – collective gatherings of pieds-noirs for religious festivals and historical anniversaries became a method for various associations ‘to maintain its coherence in the present by according individuals a predictable set of occasions through which to interact and (re)affirm their existence as a collective’ (Eldridge 2016: 120).

Ascension Day is one of the most important dates in the pied-noir calendar, where thousands have gathered in the Nîmes suburb of Mas-de-Mingue to perform an annual pilgrimage and procession. How and why did this practice come about?

In 1965, a statue of the Virgin Mary was installed in Mas-de-Mingue, having been transported from the Notre-Dame de Santa Cruz in Oran. A high number of pieds-noirs had settled in the area, making it the ideal place for the re-enactment of the Ascension Day pilgrimage which once took place in Oran.

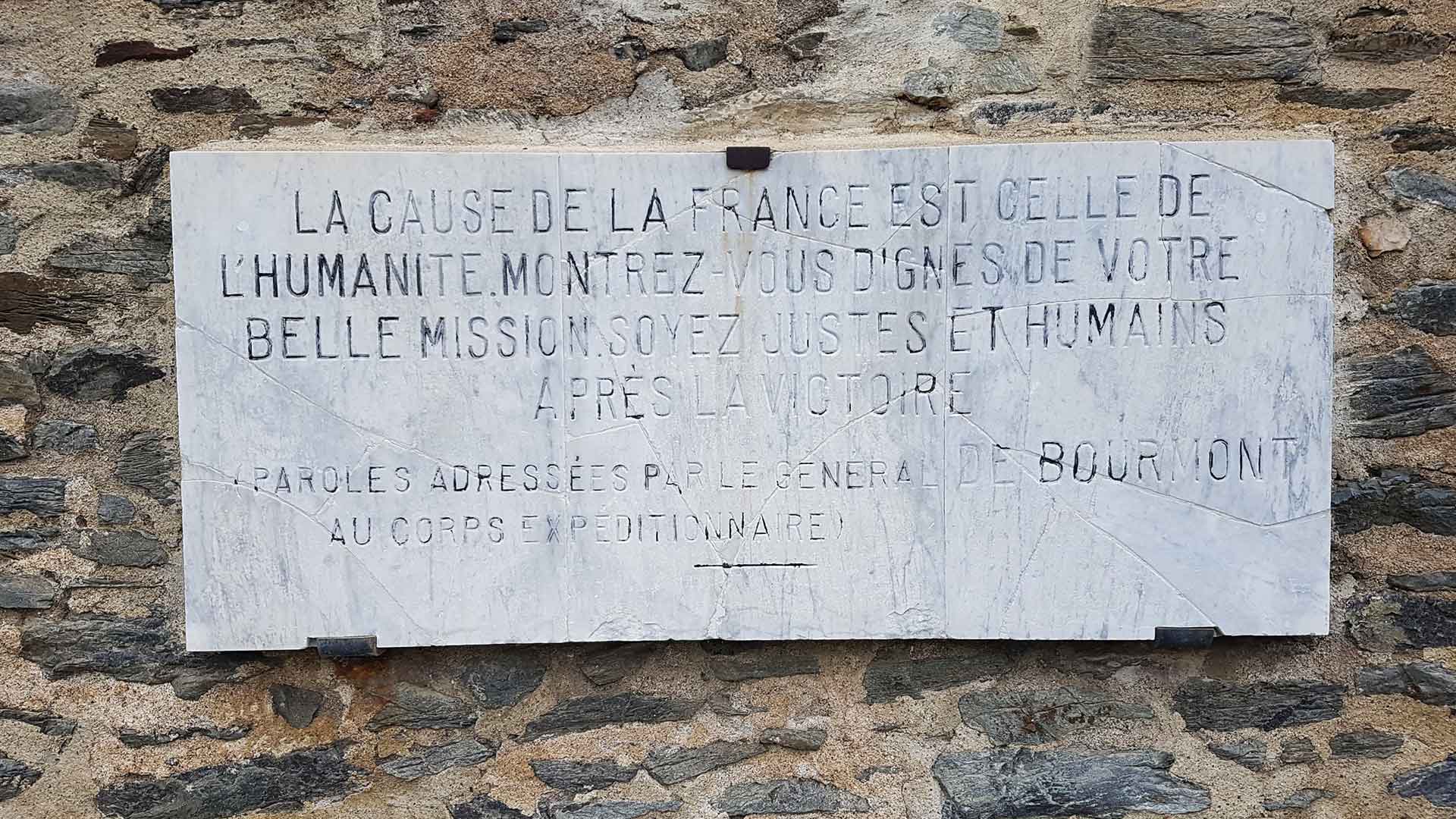

Over a century earlier, in 1849, a deadly cholera epidemic had taken hold of Oran. Desperate for its end, a group of Spanish-Catholic settlers undertook a procession of the Virgin Mary to the summit of the Aïdour Mountain overlooking the city and its port. According to local legend, rain then fell shortly after on November 4th, washing away the plague and bringing an end to the city's calamity. In recognition of the Virgin’s miracle, the Spanish-Catholic community built the Basilica of Santa Cruz on top of the mountain and re-enacted the miraculous procession every year. (The same plague is said to be the inspiration behind Albert Camus’s allegorical plague in La Peste).

With the Virgin Mary of the Basilica of Santa Cruz now repatriated to Nîmes, the recreation of the Oranais tradition attracted crowds of former settlers beyond the original Spanish community from Oran. An initial gathering on 19 March 1966 drew a crowd of 7,000 pieds-noirs which swelled to 18,000 the following year. In the 1980s, at the peak of pied-noir activism, the procession attracted hundred of thousands (Michèle Baussant 2002). The large numbers attest to the fact that, for the former settlers, Nîmes is more than a religious festival. It is an opportunity for families, neighbours, and communities to reconnect, now in France.

The sheer numbers of attendees raised the problem of simply finding each other in the crowd. Around the site in Mas-de-Mingue and its surrounding roads, these moments of ‘retrouvailles’ were facilitated by mounted cardboard signs, bearing the colonial-era names of neighbourhoods in Oran and its region. The signs were accompanied with maps and pictures that visitors were encouraged sign and annotate. Beyond a practical way of organising the crowds of several thousand ‘pieds-noirs’, the signs also symbolically reproduced an imagined Algerian territory that no longer exists. For Marlène Albert-Llorca, these meeting points are essential to this process of reconnecting with the lost territory – visitors are invited to write their names and addresses (of colonial Algeria) alongside the maps and place name: ‘In this way, the neighbourhood finds itself full of people again, year after year, through the magic of writing’ [Le quartier se trouve ainsi en quelque manière repeuplé, année après année, par la magie de l’écriture] (2004: 171).

However, Albert-Llorca also notes that the practice of the pilgrimage does not lend itself to the transmission of memory to new generations. The staging and practice of the pilgrimage centres on those with lived memories of settler communities and the exodus who, as time passes, are less and less numerous every year. While the memory activism of pied-noir associations have worked to foster a postmemory of settler communities, the prolonged future of this narrative in the 21st century is still not certain.

In 2018, one attendee noted ( when interviewed by France Bleu in 2018) that the pilgrimage provides a way for her family to reconnect with loved ones, but laments how this has not been picked up by younger generations:

The role of religion is important because the Virgin of Oran, if we think of Albert Camus, is important. It’s the Virgin that saved lives from the plague! And it’s our Virgin. For them [the pieds-noirs], it is as if it’s a little bit of Algeria. It allows them to reconnect with their friends, family … food as well, we have charcuterie, cakes.

I think it’s a shame that the younger generation don’t follow this movement. I have no photos, I have no material memories, I only have what my parents told me. When you leave with nothing, when you leave everything behind, you can never get back what has been lost.

I’m a teacher. One time a colleague, another teacher, was saying ‘We’re going to go up into my grandmother’s attic, we’re going to go through what’s there’ all that. I don’t have such luck. I can’t look through my grandmother’s attic, because there isn’t one. (Nathalie, 53)

From the specificity of the Catholic-Spanish community of Oran, the pilgrimage to Mas-de-Mingue has come to symbolise the entire pied-noir community in France. As Amy Hubbel puts it, ‘the church now represents Pieds-Noirs from all regions of Algeria. Individual attachment to the icon is effaced in favour of communal representation’ (Hubbell 2015: 211). This idea of selective remembrance and re-appropriated practices in exile echoes an earlier study by Susan Slymovics who suggested that the ‘traditional’ pied-noir pilgrimage relies on colonial-era stereotypes and nostalgia: ‘An obvious example is the representation of the Arab who is literally maintained on the periphery, placed apart and hidden in his folkloric tent and relegated to the role of restaurant service’ (Susan Slyomovcis 1995: 347).

For Michèle Baussant, the pilgrimage gives space to this colonial re-imagining as a form of ‘counter-history’ and nostalgia which would be absolutely rejected elsewhere: ‘The nostalgic element may indeed be present, but the Pieds-Noirs have nonetheless adopted these pilgrimages as a ‘legitimate’ outlet for expression of emotion and memories which in other places and circumstances would find no audience or would generally be considered highly inappropriate’ (Baussant 2016: 223).

However, as the numbers of attendees at these gatherings fall lower and lower, the question of transmission remains: Can this experiential re-imagining of Algerian territory in France be transmitted to younger generations with no lived connection to Algeria? Does this selective, nostalgic, and performative practice of pied-noir memory have a future?