Commemorating the First World War in Colonial Algeria

In the decades following the First World War, public squares and sea-front promenades in Algeria were visually transformed by the presence of monuments aux morts. These commemorated the European settlers, and native Arab, Berber, and Jewish populations who were killed while fighting in Europe between 1914-1918.

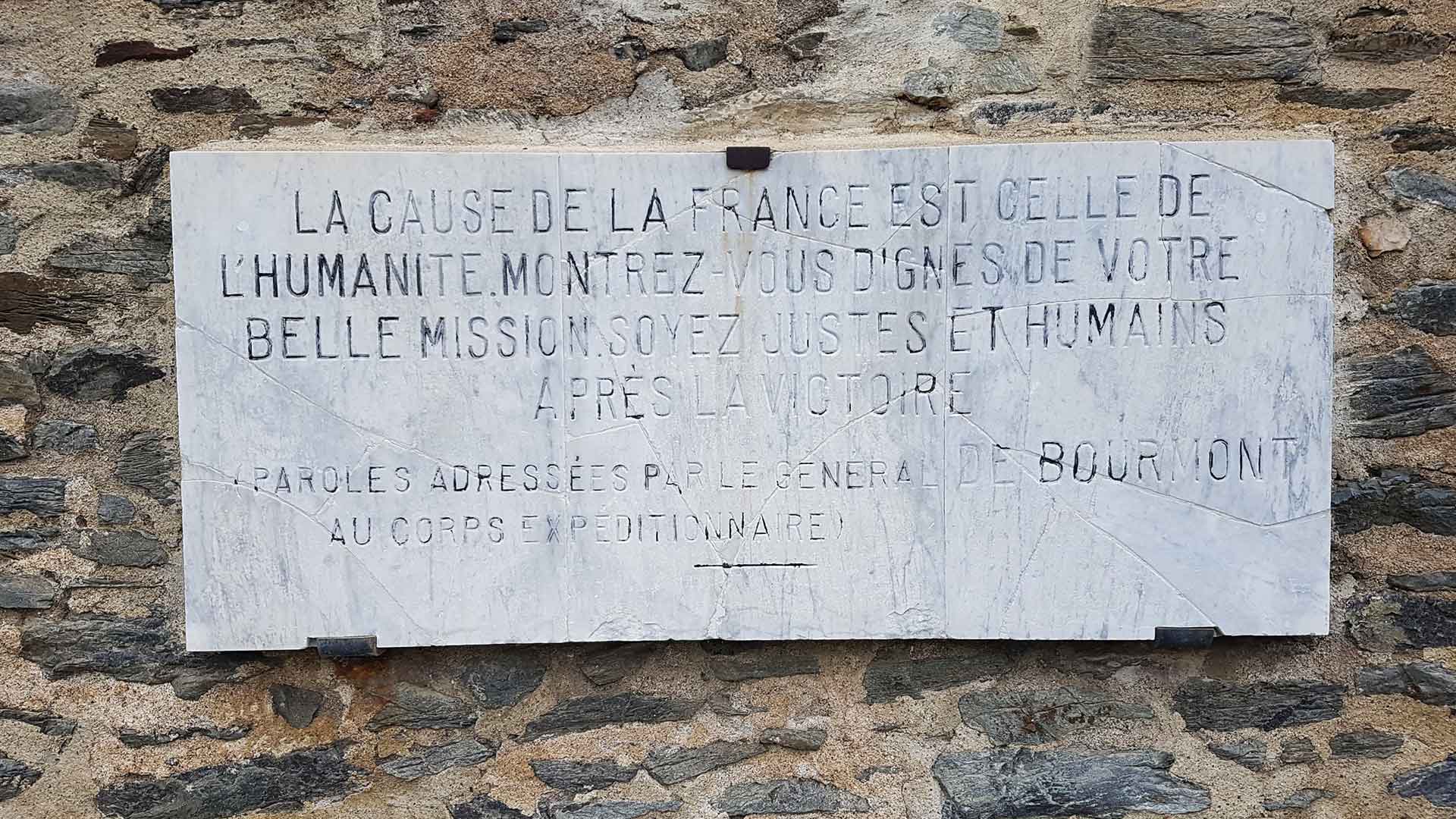

On the one hand, the monuments were designed to be very similar to their metropolitan counterparts appearing in towns and villages in France. This visual unity helped to formalise a shared sense of lieux de mémoire and, consequently, reinforce the ‘Frenchness’ of Algeria. On the other hand, many of these commemorative sites were inaugurated to mark other, specifically colonial anniversaries: namely, the centenary of the invasion of Algeria in 1930. As a result, First World War monuments in Algeria, especially, reveal the layering of different kinds of meanings and memories, even in the most recognisably 'French' examples. Following the Second World War, their commemorative capacity expanded to recognise the French and Muslim soldiers who died liberating France. However, with the rise in Algerian nationalism and the outbreak of the Algerian War of Independence, these monuments acquired new meaning as contested sites of both European hegemony and the struggle for Algerian independence.

In this series of blog posts, we will explore the trajectories of some of these monuments and statues that contributed to the ‘visual economy’ of colonial Algeria. It will cover where, when, and why they were erected in colonial Algeria, but also how these colonial lieux de mémoire were repatriated in France or acquired new meaning in the wake of decolonisaiton.

The following briefly describes three monuments aux morts from Algeria. They were all built under French colonialism during the inter-war period to commemorate the war dead of the 1914-1918 conflict. However, they have all led different afterlives following independence, reflecting the different symbolic approaches to French colonisation, decolonisation, and repatriation to the métropole.

Constantine

Before the Independence referendum of July 1 1962, First World War monuments aux morts in Algeria faced a campaign of destruction, or the ‘statues war’, by nationalist activists who recognised these lieux de mémoire as symbols of colonial power that had to be effaced with the urgent project of decolonising Algeria public space (Andrea Smith 2013: 70). It was in this atmosphere that provisions were made by the French Army's Service Historique de la Défense to ‘repatriate’ the monuments, as well as the settlers, of French Algeria.

However, not all monuments could be repatriated. The enormous triumphal arch of Constantine, for example, was never targeted in a meaningful way during the ‘statues war’ and remains a prominent landmark.

Overlooking the Rhummel gorges, the foundation stone for this monument was laid only a week after the 1918 armistice. However, the final imposing 21m tall arch was only officially inaugurated in 1930, the centenary year of French Algeria. In terms of design, the monument closely resembles its metropolitan counterparts and inscribes the names of 844 men – Algerian Muslims and Jews, as well as European settlers – from Constantine who died during the war.

Four busts of the celebrated maréchaux of the Great War were also displayed under the arc: Foch, Joffre, Franchet D’esperey and Pétain. In 1944, two years after Operation Torch which ended Vichy’s grip on French Algeria,Pétain’s bust was removed, leaving the other three monuments. This is an intriguing detail, given President Macron’s recent comments regarding the Pétain’s First World War record, during this month’s centenary commemorations in France.

On 11 November 2015, the 97th anniversary of the 1918 armistice, a ceremony led by Hocine Oudah, Wali of Constantine, with the ambassadors of France and Germany in Algeria, commemorated 'tous les combattants d’Algérie, victimes de ce conflit'. A plaque in Arabic and French now marks the ceremony, uniting representatives of Algeria, France and Germany, inside the arch. The ceremony echoes some of the colonial era commemoration which stressed the diversity of the soldiers who had died for France, reinscribing the colonial 'fraternity of arms'. However, the addition of the German ambassador also re-frames the focus on Franco-German reconciliation, rather than on Franco-Algerian relations.

Oran

From 1927, Oran’s Avenue Loubet was the site of Albert Pommier’s sculpture, Monument de la Victoire. The 8m-tall monolith, topped with three figures, towered over the avenue until the end of the War of Independence when the figures were removed and repatriated. Two of the figures represented French poilus stand with their backs to the sea, surveying Oran and the rest of Algeria. Behind them, almost hidden from view, the figure of an Algerian tirailleur, sitting and holding a rifle, stares out towards France on the other side of the Mediterranean.

For Dónal Hassett, the organisation of these figures reflects a 'clear sculptural hierarchy, reflecting the social hierarchy of colonial society [...] in a monument which barely pays lip service to the fraternity of arms, while simultaneously highlighting the imperative of safeguarding the dominance of the European community' (2018: 157).

During the Algerian War of Independence armistice ceremonies continued to be performed at the base of the monument, which increasingly also commemorated 'those who had died at the hands of the FLN' (2018: 161). Following Algerian Independence, a delegation of local councillors from Lyon negotiated the transfer of the monuments to Lyon (Oran's twin city) in 1967. Leaving the pedestal behind, the three figure were re-erected at a less imposing height in a modest public garden between apartment blocks in the La Duchère suburb of Lyon. In Algeria, the pedestal has since been re-imagined as the 'Stèle du Maghreb.'

The monument’s repatriation to Lyon is no accident. The mass migration of the European settlers to France in 1962 coincided with a major building project in the suburb of La Duchère. With the political backing of the new mayor of Lyon, Louis Pradel, a third of these new homes were reserved for the arrivals from Algeria. In certain areas, repatriates accounted for over half of the population of La Duchère. As the former twinned-city of Oran, the Lyonnais mayor also selected the Monument de la Victoire to mark the history of Lyon’s newest residents. The monument was inaugurated 13 July 1968, footage of which you can watch below, and in November that year repatriate groups held their own ceremonies which stressed, not just the Algerian and French war dead of the First and Second World Wars, but their commitment to French Algeria. In Hassett's words, these ceremonies 'sought to cloak the defence of colonial rule in the legitimacy of the wartime fraternity of arms' (2018: 165).

Sidi-Bel-Abbès

Perhaps unsurprisingly, there is a very close relationship between First World War monuments and the French army. For the Legion Étrangère (present in Sidi-Bel-Abbès since 1843), First World War commemoration is inseparable from a recognition of France’s colonial project.

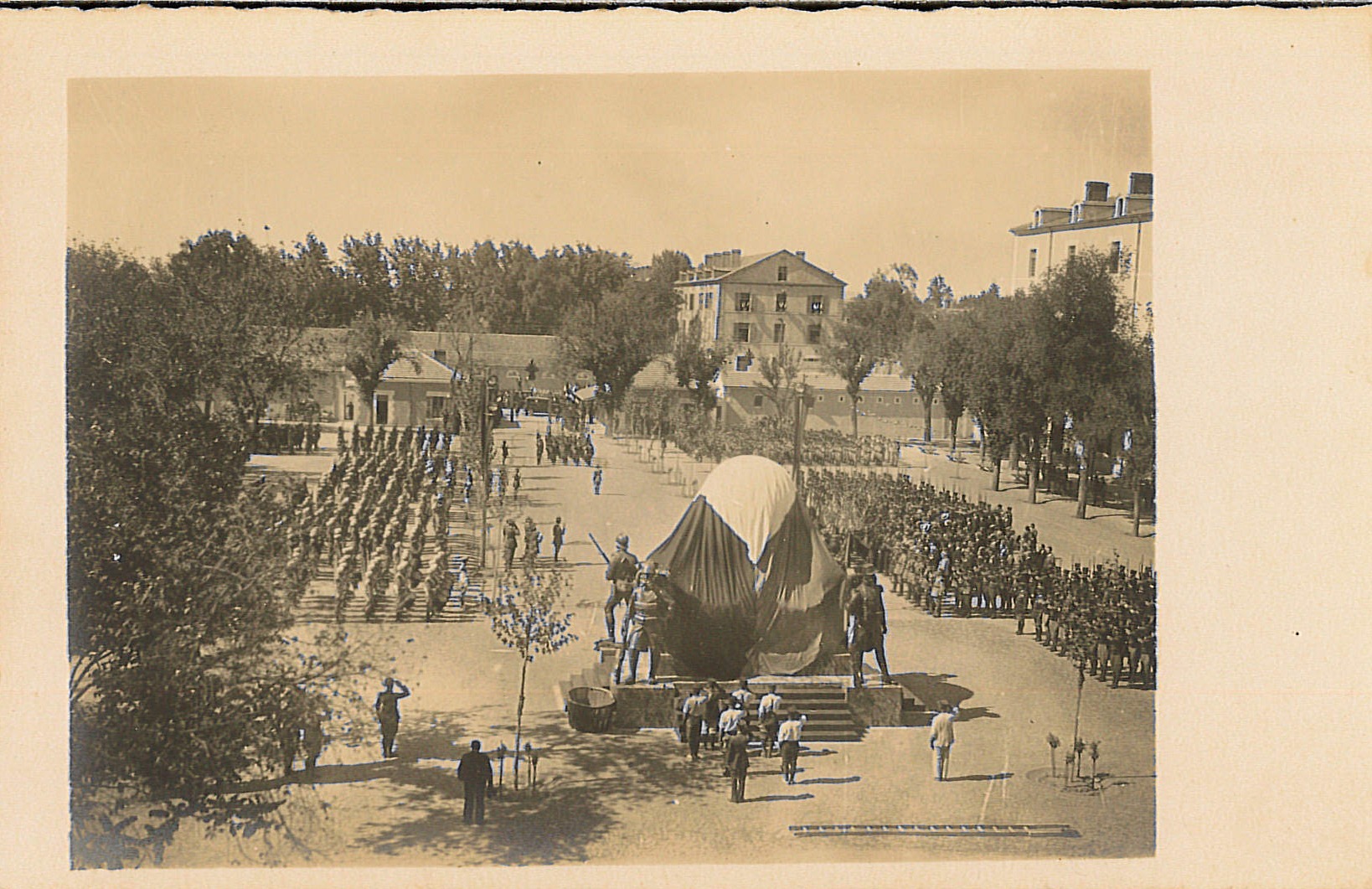

In 1931, an elaborate monument was inaugurated in the Legion Étrangère’s headquarters to commemorate the war dead and the centenary anniversary of the Legion. Embedded on a raise plinth, the monument’s striking globe stresses the Legion Étrangère’s past and desired future, as a colonial power with global ambition.

Inauguration 30 April 1931

Somewhat ironically, then, the monument’s international career ended when it was returned to France in 1966. Along with the Legion’s salle d’honneur, which also honoured the memories of legionnaires killed in combat, it can now be found in the town of Aubagne, near Marseilles. Rather than a public site of memory for pieds-noirs this monument is closely linked to the Legion Étrangère and its museum, serving as a backdrop to military parades and commemorative ceremonies.

Algiers

Perhaps the most well-known example of a First World War monument aux morts in Algeria is Paul Landowski’s Pavois in Algiers. Unlike those mentioned above, the monument was neither destroyed, ignored, or repatriated. The next blog post will discuss the strange fate of this famous monument, revolutionary aesthetics and unexpected returns of the past in the urban palimpsest of Algiers.