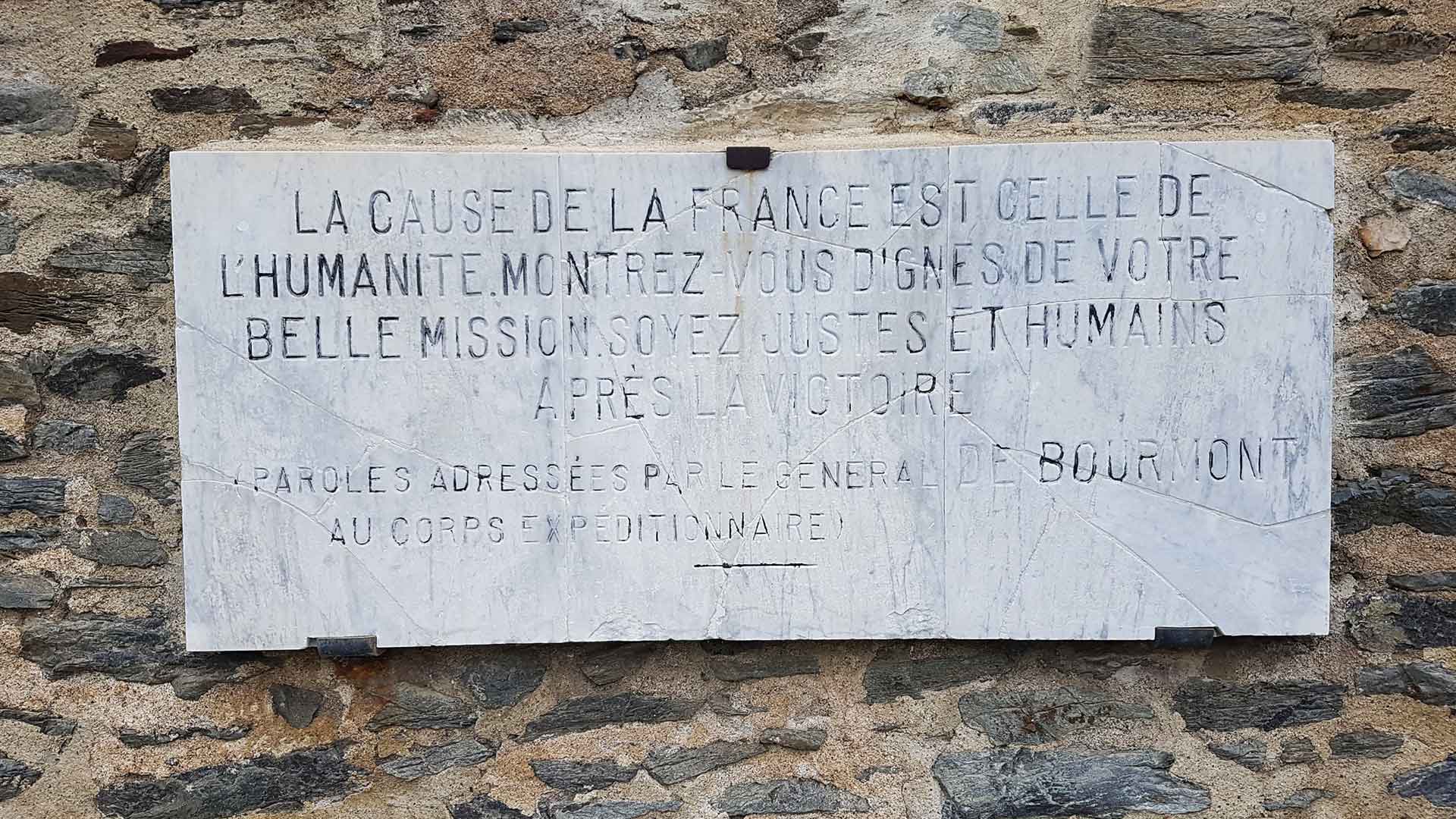

The Santa Cruz pilgrimage, Nîmes

Albert Camus’s La Peste (1947) imagines the city of Oran, enclosed and ravaged by an outbreak of plague, as a parable of the German occupation of France during the Second World War. In the novel, the narrator laments the banal, monotony of this calamity:

The truth is that nothing is less sensational that pestilence, and reasons of their very duration great misfortunes are monotonous (London: Penguin 1960, p.148)

['C’est que rien n’est moins spectaculaire qu’un fléau et, par leur durée même, les grands malheurs sont monotones.’ (London : Methuen 1962, p. 198)]

Nonetheless, La Peste is inspired by an actual Oranais plague from a hundred years earlier, one that is remembered in spectacular ways by pied-noir communities in France. According to the legend, the deadly cholera epidemic that was gripping Oran in 1849 finally broke when the desperate citizen undertook a procession with the Virgin Mary to summit of the Aïdour Mountain overlooking the city and port. Rain fell on November 4th, washing away the plague. In recognition of the Virgin’s miracle, the Spanish-catholic community built the Basilica of Santa Cruz atop of the mountain, the miraculous procession re-enacted annually.

Since the 1965, pieds-noirs from Oran and beyond have gathered at the new Notre-Dame de Santa-Cruz in Nîmes to mark Ascension Day with another procession with the same Virgin Mary of Santa Cruz. The pilgrimage and re-performance of the ritual is a powerful way to affirm a connection with a shared narrative, origin, and sense of belonging. Indeed, Amy Hubbell notes that, in re-staging a memory from a specifically Catholic and Oranais tradition, the pilgrimage has come to encompass a collective point of reference for many pieds-noirs.

In spite of the architectural and geographic shifts in the representation of the church, Notre-Dame de Santa-Cruz is solidified as a communal icon. The church now represents Pieds-Noirs from all regions of Algeria. Individual attachment to the icon is effaced in favour of communal representation (Hubbell 2015: 211).

There is a sense that these specific, cultural markers of various facets of pied-noir identity – Oran, the plague, the miracle, the Virgin, even Camus – are amalgamated in the course of the ceremony, as suggested by the testimony of one of the ritual’s participants (interviewed by France Bleu in 2018):

The role of religion is important because the Virgin of Oran, if we think of Albert Camus, is important. It’s the Virgin that saved lives from the plague! And it’s our Virgin. For them [the pieds-noirs], it is as if it’s a little bit of Algeria. It allows them to reconnect with their friends, family … food as well, we have charcuterie, cakes.

I think it’s a shame that the younger generation don’t follow this movement. I have no photos, I have no material memories, I only have what my parents told me. When you leave with nothing, when you leave everything behind, you can never get back what has been lost.

I’m a teacher. One time a colleague, another teacher, was saying ‘We’re going to go up into my grandmother’s attic, we’re going to go through what’s there’ all that. I don’t have such luck. I can’t look through my grandmother’s attic, because there isn’t one. (Nathalie, 53)