The Landowski-Issiakhem Pavois

Monument aux morts

Inaugurated on Armistice day 1928, the Algiers Monument aux morts was originally designed by Paul Landowski, himself a veteran of the First World War, and creator of the famous Christ the Redeemer statue in Rio. The limestone monument shows a wounded body being carried by three horsemen, a French cavalryman, an Algerian spahi, and a winged Victory. Behind them, two women and two old men belonging to the two communities mourn their children who are ‘morts pour la France’. Various bas-reliefs at its base record a mixing of Europeans and Algerians in the trenches and bears the names of 10,000 men from Algiers. Located in the administrative centre of the colonial capital, Landowski’s design purposefully represents the communities of European settlers and indigenous Algerians, supporting the colonial narratives of a fraternity of arms.

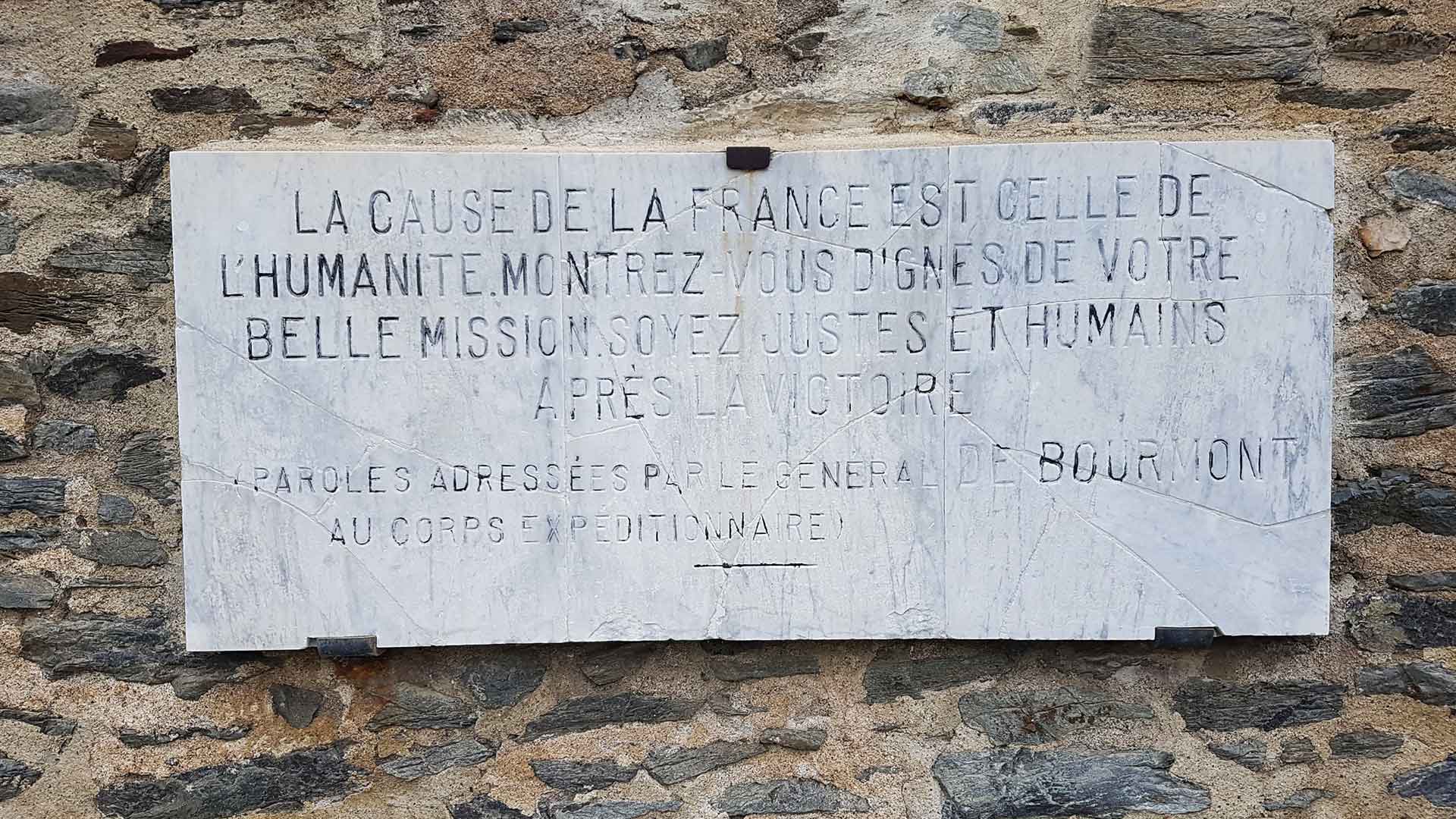

However, two years after the monuments inauguration, throughout Algeria, settler society celebrated the centenary of the French invasion. In June 1830, a 20 km torch relay connected Landowski’s war monument to the Sidi-Ferruch centenary stèle (now in Port-Vendres, France). In this way, the monument’s acknowledgement of the sacrifice made by Algerian soldiers in the First World War was subsumed to the celebration of Algerian defeat and subjugation. For Dónal Hassett, Algiers monument represents the duality of colonial authority which symbolically recognises the sacrifice of Algerian soldiers, without promising material benefit or political rights:

The Algiers war memorial became a site where the colonial authorities and their allied in the municipal administration could embrace a commemorative discourse that celebrated the fraternity of arms of the colony’s different communities, while carefully avoiding any suggestion that this fraternity should morph into a form of equality. (Hassett 2018: 156-7)

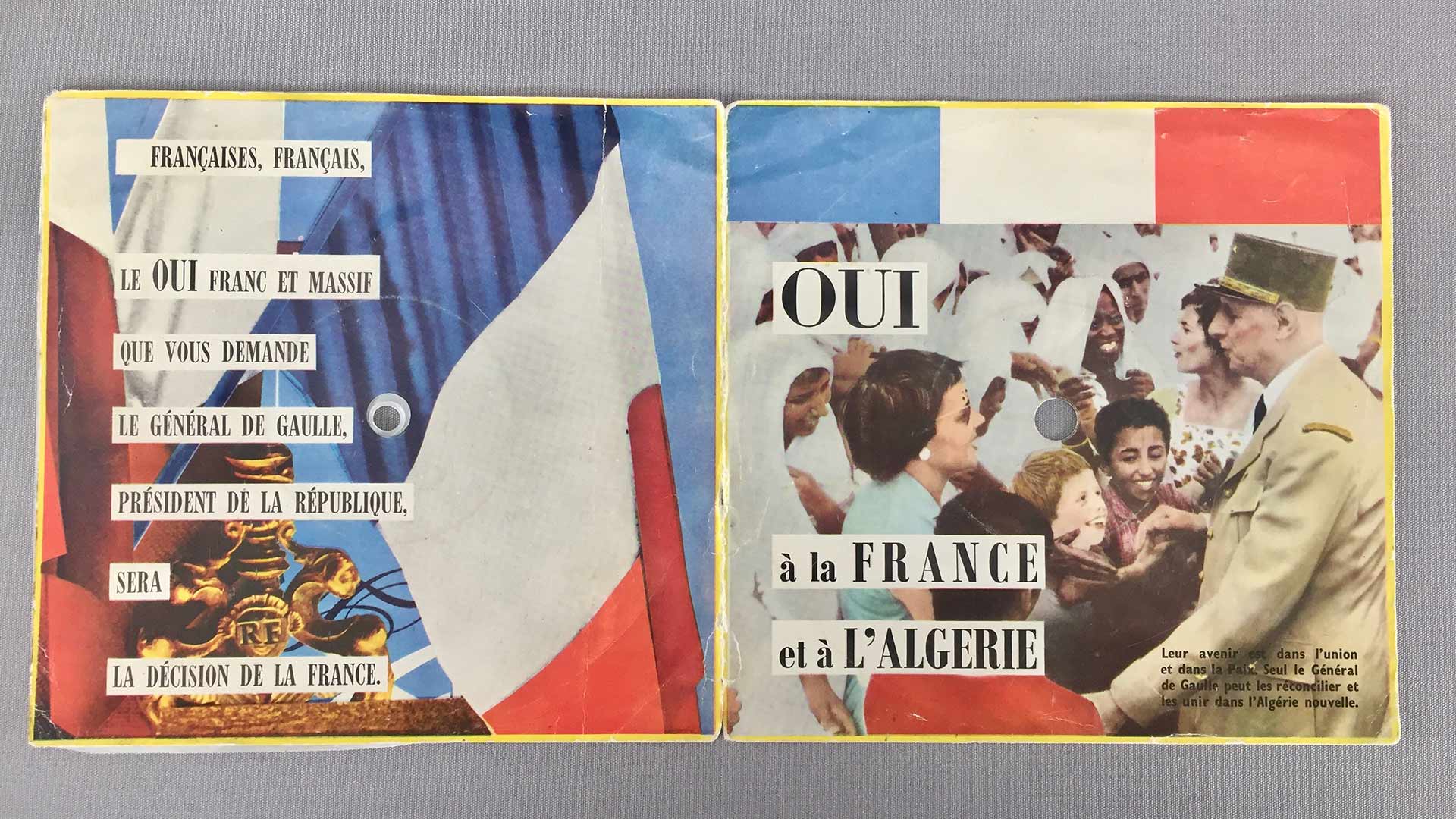

During the Algerian War of Independence, the monument’s role as an endorsement of colonial heritage became increasingly important, developing from a site of commemoration to a rallying point for protest for angry settlers, frustrated by the war’s progress. Angry crowds met the Socialist Premier Guy Mollet when he visited Algiers, and laid a wreath at the war memorial, later shredded by the protesters who viewed him as a proxy for the deeply unpopular new Governor General, Catroux.

After independence

The new Algerian government was keen to reclaim the visual economy of public space in Algeria. Nowhere was this more pressing than in Algiers, the new country’s capital and ‘mecca of revolutionaries’. However, for 16 years, the monument aux morts was left largely untouched. The engraved names had been surreptitiously chipped away over the years, but the monuments recognition of the blood sacrifice made by Algerians largely supported the FLN narratives of French exploitation and failed promises following the two World Wars.

Tolerance for the monument ended in 1978 as the city prepared for the All-Africa games and decided to remove the monument. It was only saved by a campaign led by the Algerian artist M’hamed Issiakhem and his collaborators, who convinced the authorities to allow Issiakhem to reclaim, and protect, this physical memory of colonial Algeria by encasing it in a new memory of Algeria's socialist revolution.

The result is a remarkable and unsettling example of Brutalist sculpture. The irregular shape of Landowski’s original monument prevented Issiakhem from constructing a uniform, monolithic structure. It bulges and swells awkwardly over the contours of the limbs and bodies of the figures of humans and horses underneath. On the outside, looking out to the bay of Algiers, is the carving of two heavy fists, breaking dramatically from their chains. In this sense, the monument registers two different temporalities at once. On the one hand, it represents the moment of revolutionary rupture from colonial oppression, the present of 1962 recorded in concrete. On the other hand, the monument's strange, irregular shape serves as a reminder of what remains entombed under the surface, a melancholic preservation of Algeria's colonial past. Issiakhem's construction is powerful because it does not succumb to either of these dominant narratives:

‘Issiakhem’s piece speaks to the deeper political truth of post-colonial identity: the past, however painful, must be acknowledged as the foundation of certain aspects of contemporary society. It clashes with the FLN’s desire to eradicate all vestiges of colonialism. Art allows a narrative complexity that defies the simplicity of official texts’ (Grabar 2014: 404)

In an unexpected return of the sculptures past, by the 50th anniversary of Algerian independence cracks had begun to appear in Issiakhem’s concrete structure. In 2012, Addlène Meddi reported for El Watan that the concrete was crumbling, and that portions of the original sculpture could be seen: faces and limbs of two of the figures began to emerge from underneath the concrete façade. In response, the city shrouded the monument in scaffolding, filled in and replaced the greying and water-streaked concrete.

The Landowski-Issiakhem is an actively evolving and rich symbol of Algier’s urban palimpsest. The Matryoshka effect of Issiakhem’s layering and entombing of this colonial-era monument has, unsurprisingly, been popular terrain for contemporary Algerian artists and sculptors.

Neïl Beloufa

From 16 February – 13 May 2018, the Parisian artist Neïl Beloufa’s exhibiton ‘L’ennemi de mon ennemi’ at the Palais de Tokyo included a model of the monument.

Reconstructing a cross-section of Issiakhem’s Brutalist block, the view is reintroduced to Landowski’s colonial commemoration of French and Algerian blood sacrifice during the First World War.

Beloufa’s social-realist reproduction of the monument underlines Issiakhem’s double achievement: in constructing a monument in celebration of the Algerian revolution, that adheres to the new political and aesthetic landscape of Algiers, the sculpture is also an act of conservation in using Landowski’s monument also it’s structural foundation.

Amina Menia

The Algerian artist Amina Menia has also been inspired by the ‘double monument’ for her 2013 work in Algerian urban space ‘Enclosed’. This documentary-based installation re-stages the evolution of this complex lieu de mémoire, fostering a dialogue between Landowski and Issiakhem that never truly happened in real life. Menia explains:

'As the third generation of artists to dialogue with this public monument, I chose to place the works of both artists in echo. Issiakhem didn’t really dialogue with Landowski or his work because he had the obligation to cover it. But I found his gesture very moving and exceptional. It is so generous on the part of an artist to respect someone’s work like this and to set it in another relation to time and history. He offered the next generation the choice (or maybe the responsibility) to admit the fate of this sculpture.

I discovered how intimately connected Issiakhem's life and work were with all the transformations that occurred in Algeria during more than 2 decades. He illustrated the sociopolitical project of the new Algerian Republic. He was always primarily a freedom fighter, before being an artist. He crystallised a certain “Algeria” that still remains today, tinted with nostalgia. He influenced a whole generation of artists, and still today, young artists claim their filiation to him.'