From Sebbar's essay 'Les femmes du peuple de mon père' (2006: 6).

References

Alloula, Malek ([1981] 2001) Le harem colonial : images d'un sous-érotisme, Paris: Séguier.

Blanchard, Pascal et al., (eds) (2018) Sexe, race et colonies, Paris: La Découverte.

Hubbell, Amy (2015) 'Filling in the Void: Leila Sebbar's Collective Archaeology of Origins', Expressions maghrébines, 14(1), pp.41-54.

Sebbar, Leïla ([2002]2006) 'Les femmes du peuple de mon père’, in Sebbar, L., Taraud, C., Belorgey, J., Femmes d'Afrique du Nord, cartes postales (1885–1930), Saint-Pourçain-sur-Sioule: Bleu Autour.

Stafford, Andy (2010) Photo-texts : contemporary French writing of the photographic image, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

Vogl, Mary (2003) Picturing the Maghreb: Literature, Photography, (Re)Presentation. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield.

Welch, Edward and McGonagle, Joseph (2012) Contesting Views: The Visual Economy of France and Algeria. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

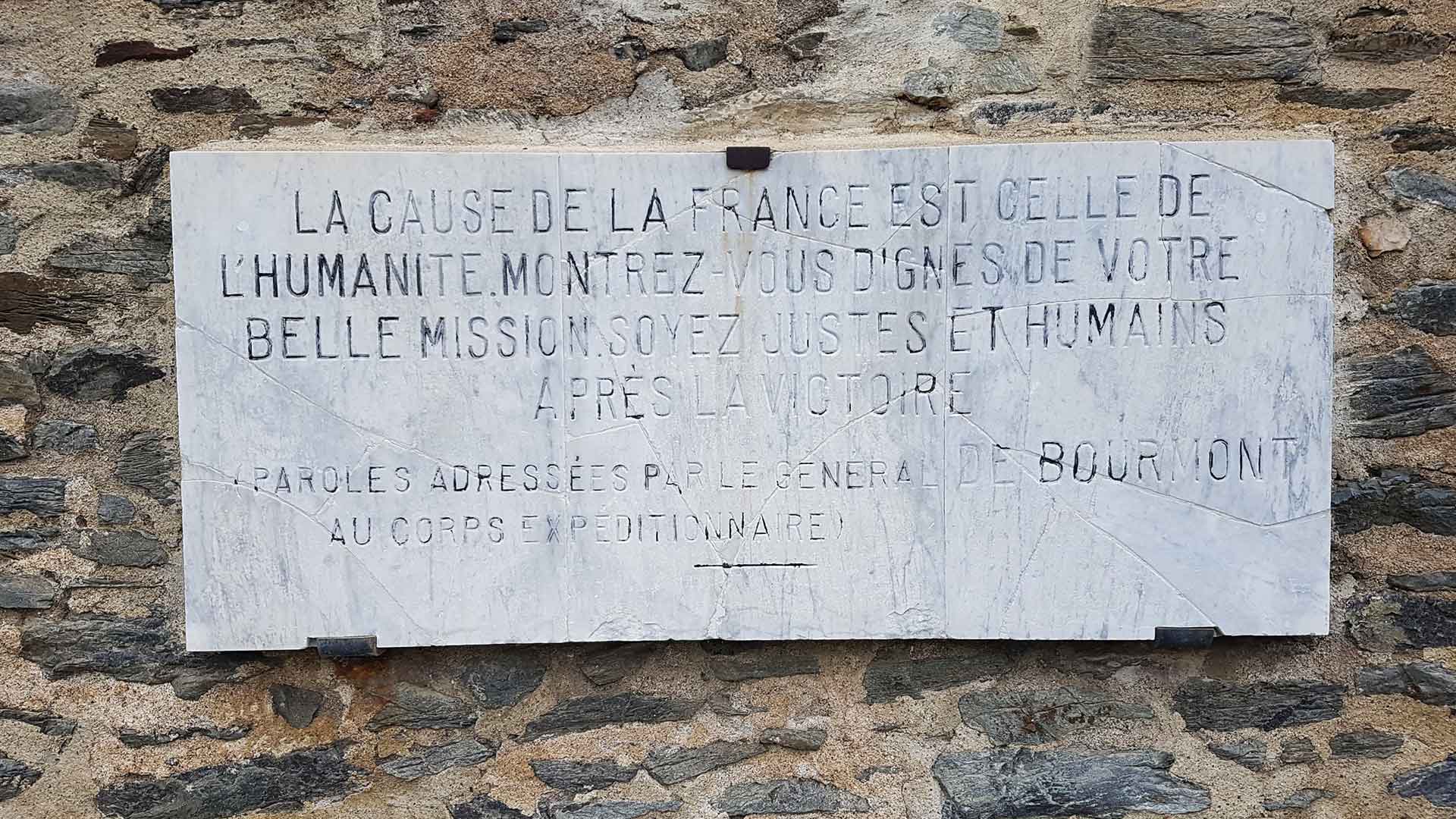

The postcards are reproduced with the kind permission of 'La Mer à Boire’ society and the Redoute Béar Museum in Port-Vendres.

Les cartes postales sont reproduites avec l’aimable autorisation de l’association 'La Mer à Boire’ et le musée à la Redoute Béar à Port-Vendres.

Postcards II: Return to sender

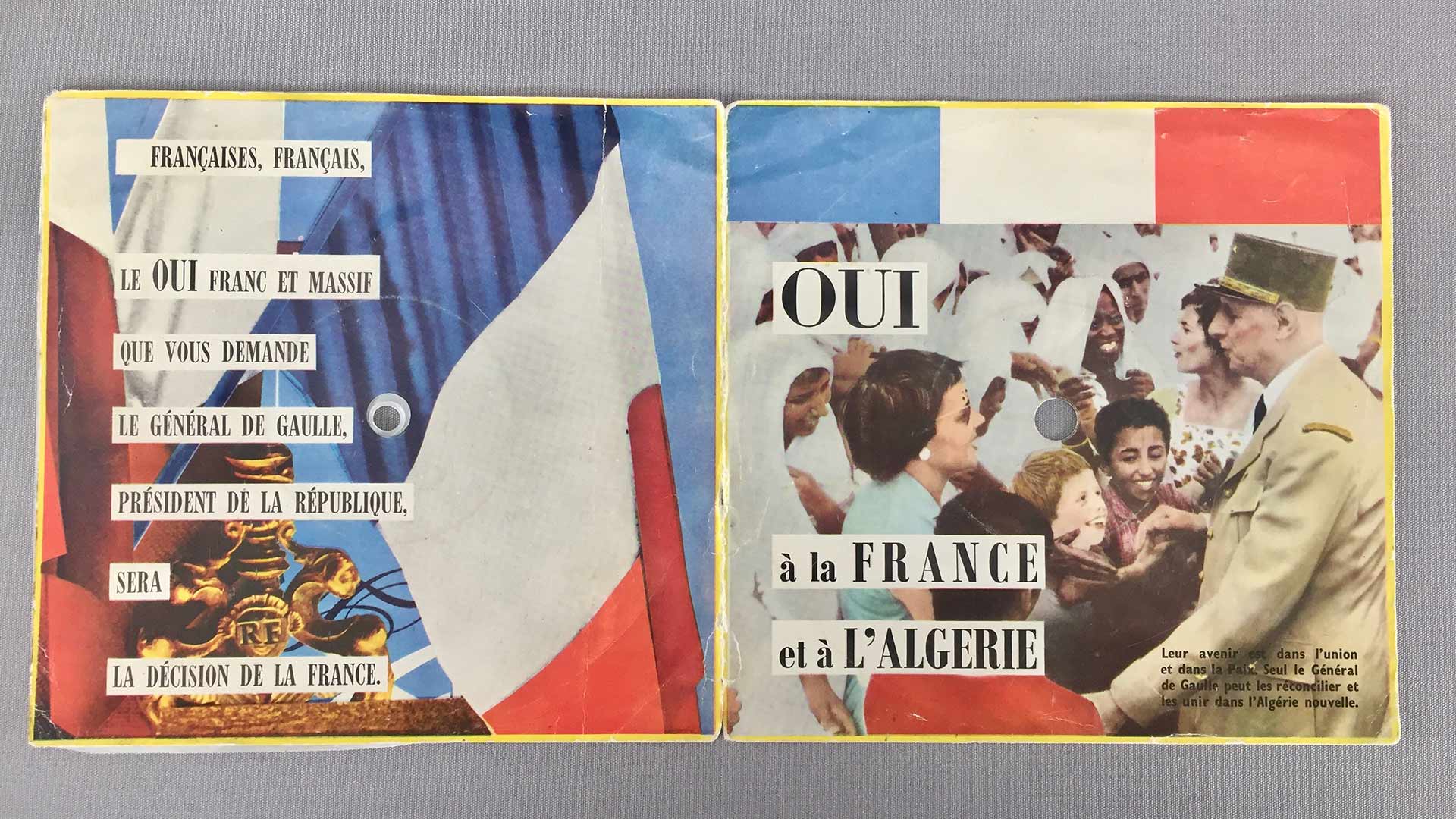

Colonial postcards have been making the headlines in the French national press. As part of the publicity surrounding the publication of Sexe, race et colonies (Blanchard et al 2018) – an enormous book which reproduces around 1200 images of sex in colonial power relations – the ongoing conversation about decolonisation in the 21st century is also considering the role played by postcards in the formation of colonial imaginaries.

Voyeuristic and palpably violent, some of these postcards are disturbing documents. Unlike the images that are reproduced as part of this project’s cartography (focused on topography as opposed to portraiture), these images are historical artefacts which testify to the ways bodies are objectified and brutalised by colonial regimes. Interviewed for liberation.fr, Pascal Blanchard notes:

Ces cartes et leurs récits - mais aussi les magazines populaires, les romans de gare ou les illustrés grand public - sont la preuve que la colonisation fut un grand «safari sexuel». On prenait les corps et on envoyait la marque de cette prise de possession sans aucune pudeur, comme des trophées.

This practice is, of course, not unique to French imperialism, and examples can be found across other colonial regimes. Interviewed in the Scroll, the historian Omar Khan notes how postcards were political tools to maintain the impression of a civilising mission in British India. In 1903 and seven years into an outbreak of bubonic plague in Bombay, British photographers were sent to photograph the city and represent that all, in fact, was well:

The postcards sort of became tools of propaganda to show that the authorities were doing everything they could, and to encourage people to still come and visit India because obviously merchants and visitors were particularly worried about Bombay, it being a port city.

Sickly, dying bodies are sanitised and even exoticised by the colonial postcard. As colonial fantasy or propaganda, these images helped to distort the material conditions of colonialism. In Sexe, race et colonies, the editors seem to underscore the way in which sexuality is at the heart of the colonial project, reducing colonised peoples to collectable objects, like the postcard itself.

However, like any visual production, these colonial images acquire new meanings and significance, as they are re-circulated, re-framed, and re-read. Postcards are particularly susceptible to this process of re-framing since they can be isolated from their original catalogue, organised by individuals to form different collections: one can, literally and figuratively, cut and paste postcards into new narratives.

In revisiting colonial era postcards, what can they tell us about the history of colonial imagery beyond its original reception?

Return to sender?

The visual ambivalence and instability of colonial postcards has been a rich arena for artists, scholars, and members of various North African communities as they revisit these catalogues and add their own take on ‘the visual economy of the French-Algerian relationship’ (Welch and McGonagle 2013: 7).

On the one hand, these postcards have reappeared in examples of postcolonial reappropriation, most notably Malek Alloula’s Le harem colonial (1981). Focusing exclusively on sexualised and orientalist images of Algerian women taken in the 1920s and 1930s, he selects and regroups these portraits under new headings in order to ‘return […] this immense postcard to its sender’ (Alloula, 1986: 5). On the other, as numerous commentators have argued, this publication seems to reinforce colonial ideologies in its uncritical reproduction of the images in a way that ‘may attract simply voyeurism rather than the reflection and criticism of the photographs that the written text demands’ (Vogl 2003: 163-4). It remains to be seen if Sexe, race et colonies goes any way to depart from this tradition critiqued by postcolonial scholars since the 1990s and early 2000s.

Textual interplay

Author Leïla Sebbar is well known for using colonial-era imagery to re-visit the history of French colonialism in Algeria. In her phototexts, Sebbar narrates an imagined history of a portrait, a photograph, a postcard through her own ‘postmemories’ of an Algeria before her birth, recalled through the stories conveyed to her by her father.

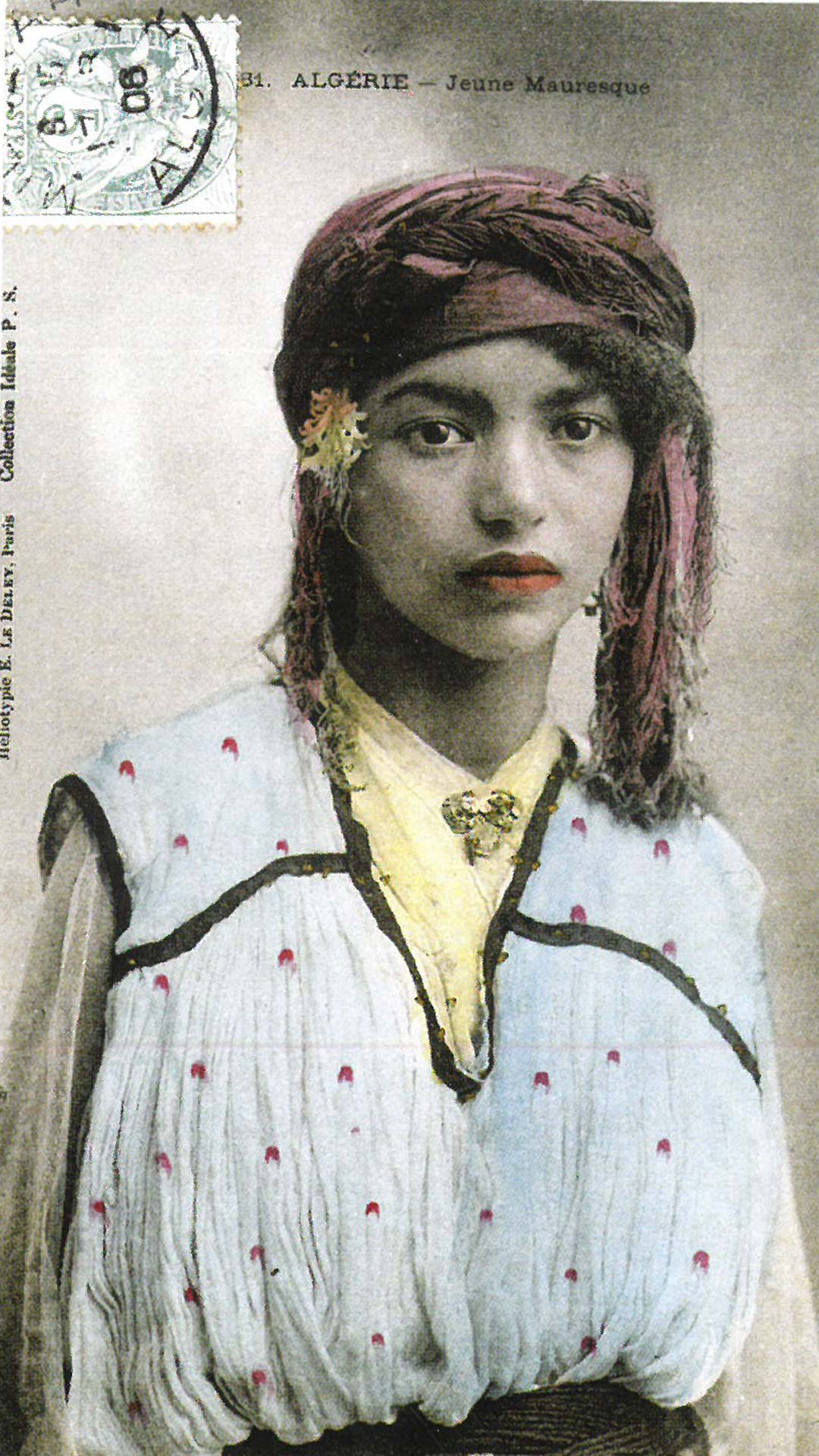

In Femmes d'Afrique du Nord, cartes postales (1885–1930), Sebbar’s essay ‘Les femmes du peuple de mon père’ opens with the image of a ‘Jeune Mauresque’. On the opposite page, Sebbar reflects :

Ces femmes sur les cartes postales ne sont pas les sœurs, les cousines, les jeunes tantes de mon père, ni sa mère. Femmes et jeunes filles sans familles ni maison, orphelines dès l’enfance. Les unes adoptées, bien ou mal, les autres abandonnées, mais la rue s’offre aux garçons, pas aux filles. Petites servantes livrées aux fermiers et aux notables, un jour mendiantes ou voleuses à la ville, avant le bordel et la prison. Mon père m’aurait raconté les orphelines de la Mission, les petites filles des Sœurs Blanche, en Afrique du Nord, missionnaires de « Notre-Dame d’Afrique ». (2006 : 7)

Sebbar recognises the temporal and historical gulf that separates her father’s family members from these women. Nonetheless as her essay proceeds, she finds way to re-imagine and re-contextualise the stories of these anonymous Algeria women and girls through her own stories. Although Sebbar’s engagement with the interplay between text and image is quite conventional (See Andy Stafford’s 2010 Photo-texts), she uses text to do what the image cannot: it offers a story for the portrait. Amy Hubbell has called this engagement between autobiography and collective histories her 'collective archaeology', an attempt 'to bring pieces of the past to the fore and enshrine them in writing' although the result may not 'render the past coherent for the reader' (2015: 52). The text never fully explains the past represented in the image, but enables some sort of excavation of it.

By the postcard's design, the only textual traces that are supposed to be left are those of the sender. Studying colonial-era postcards, the traces of the people who sent them are visible by their scribbled notes, addresses, and the stamps of the postal system marking their passage. In writing alongside the images of postcards, Sebbar is also adding another textual layer to what is essentially already a phototext: it is an indirect, imperfect, but nonetheless important attempt to write in the imagined perspective of the ‘jeune mauresque’.