References

Prochaska, David (1990) ‘The Archive of Algérie imaginaire’, History and Anthropology, 4:2, 373-420.

Schor, Naomi (1992) ‘Cartes Postales: Representing Paris 1990’ Critical Inquiry, 18:2, 188-244.

Welch, Edward and McGonagle, Joseph (2012) Contesting Views: The Visual Economy of France and Algeria. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

The postcards are reproduced with the kind permission of 'La Mer à Boire’ society and the Redoute Béar Museum in Port-Vendres.

Les cartes postales sont reproduites avec l’aimable autorisation de l’association 'La Mer à Boire’ et le musée à la Redoute Béar à Port-Vendres.

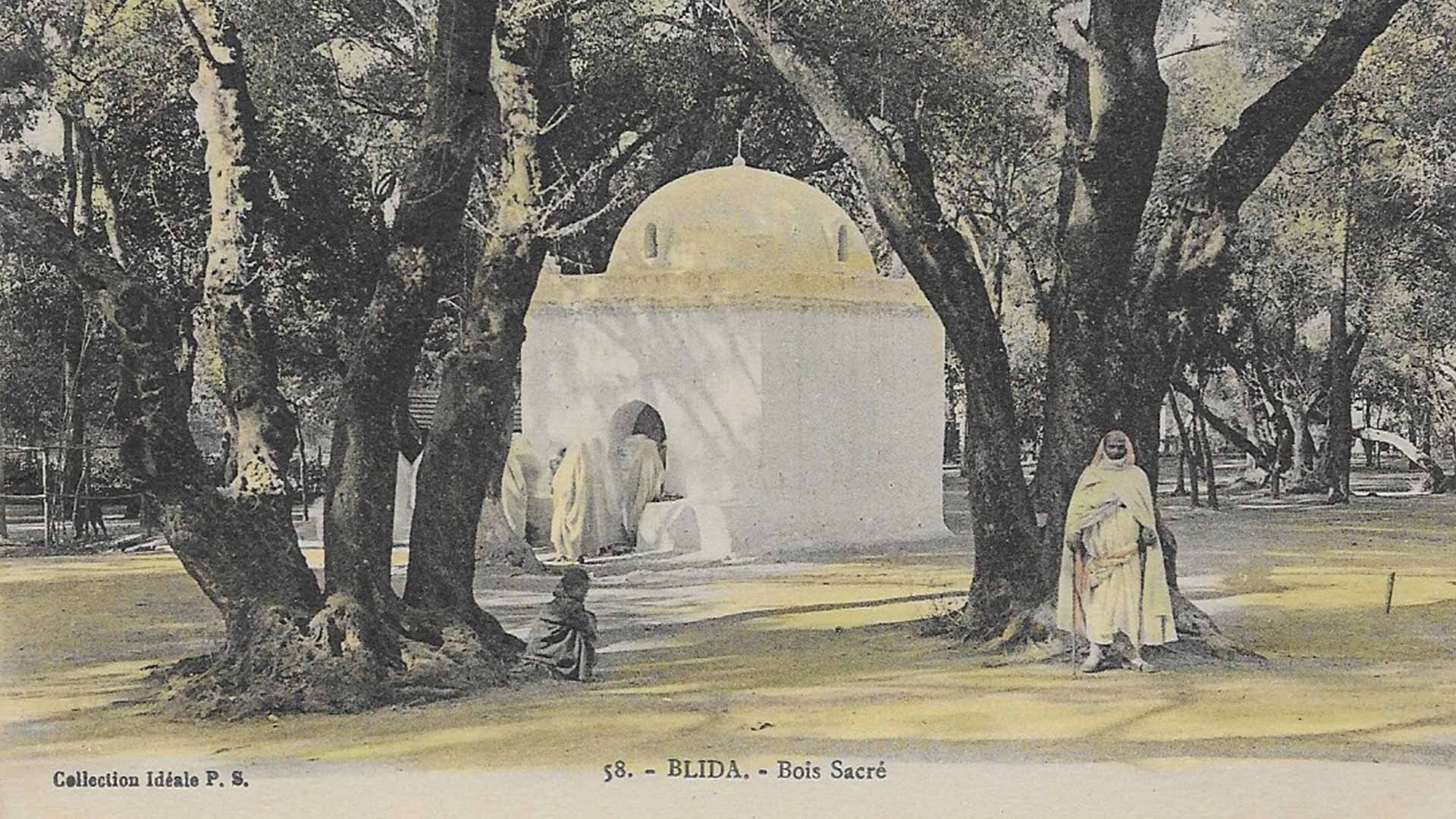

Postcards I: Colonial imaginaries

In this series of blog posts, we will focus on the images of colonial Algeria that circulated with the proliferation of postcards from the late 19th century. Photo postcards have been instrumental in the reproduction and recirculation of colonial imagery ever since they became accessible commodities in the late 19th century. Images of the ‘exotic’ and ailleurs are part and parcel of what made postcards of colonial Algeria appealing to contemporary French audiences, in particular white bourgeois women, who were keen to consume erotic images of Algérie française (DeRoo 1998).

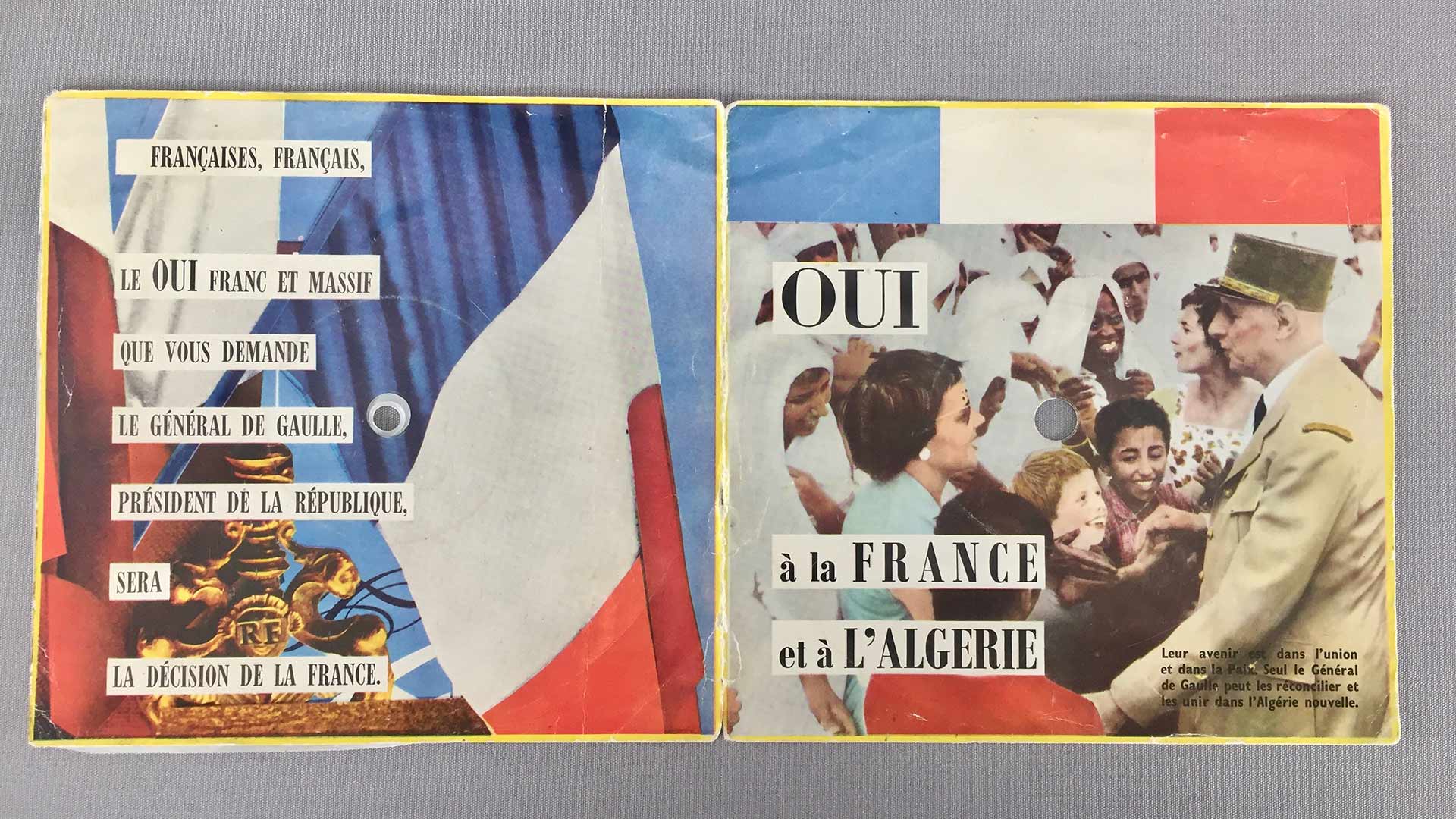

However, these images have also led significant afterlives in the post-colonial period in new collections and publications with various aesthetic and political outcomes. In briefly sketching out the trajectory taken by colonial images in the re-circulation of postcards as a form of postcolonial memory, we can begin to contextualize our own representation of some of these postcards, found in the Musée Sidi Ferruch in Port-Vendres near Perpignan, by integrating them into the Cartography Of Exile.

Big Business

At the turn of the 20th century, France witnessed a boom in the production, circulation, and collection of postcards. According to David Prochaska, postcard production grew from 8 million in 1899 to 60 million in 1902 (1990: 375). As modern France began to represent itself photographically to the world, the role of colonised territories in the visual reproduction of the nation came into focus.

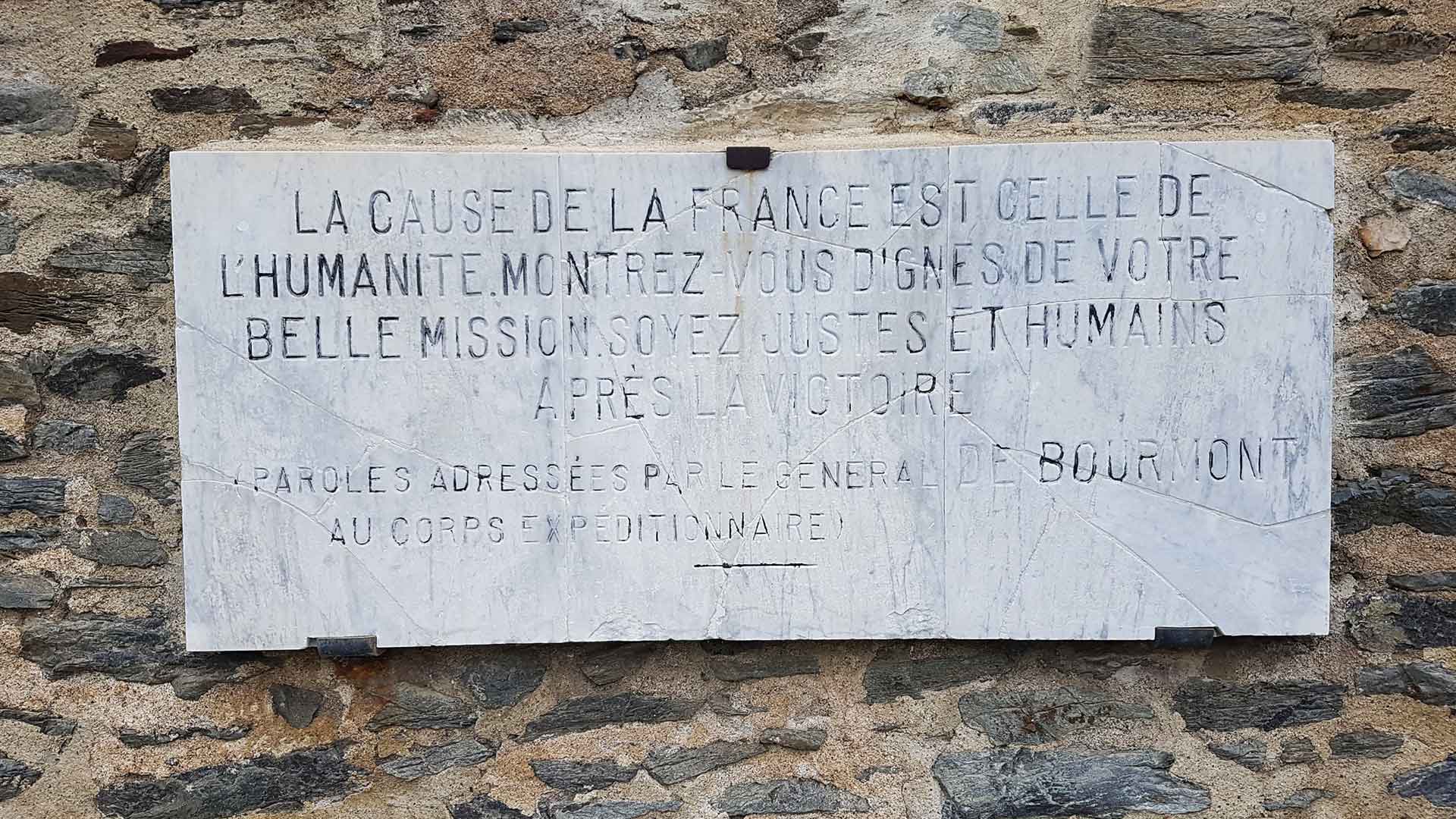

This was particularly the case for French Algeria, unique in its status as a French settler colony. The proliferation of photography in the 19th and 20th centuries became essential for the production of an ‘Algérie imaginaire’ (Prochaska 1990) for those living both inside and outside French Algeria. Deeply entrenched with colonial hierarchies and orientalist fantasy, the cards purported to show an authoritative view of daily life in the colony. Relatively cheap and collectable, postcards helped to popularise certain forms of imperial knowledge which were further crystallised by global events such as the Exposition Universelle of 1900 and the Exposition Coloniale Internationale of 1931, where these images were displayed, marketed, and restaged.

Two of the largest companies producing postcards in the early 20th century were Neurdein et Cie (cards marked with ND) and Léon et Levy (cards marked with LL). A considerable portion of their catalogues represented French colonies, including Algeria.

Sponsored by the French state to take photos of the landscapes and peoples of Algeria (neatly divided into coloniser and indigenous populations), the Paris studio of les frères Neurdein was one of the major producers of Algerian postcards from the 1890s. However, the Frenchness of this industry was suppressed in the marketing of these images to customers: ‘understood by the French to originate from the colony and to reflect the sensibilities of the indigenous population’ (DeRoo 1998: 146). You can learn more about its role in the production of colonial postcards, here.

Neurdein’s chief competitor was Léon et Levy, later Maison Lévy et Ses Fils, who also produced many of the colonial postcards which continue to be reproduced throughout the 20th century. For example, Malek Alloula Le harem colonial (1981) reproduces many of the orientalist scenes staged in LL postcards. Having been awarded photography prizes since at least 1855, around 1919 they merged with Maison Neurdein, which explains why ND and LL cards will often be found together (Schor 1992: 206-7).

Constructing the colony

The concentration of these businesses in Paris, the imperial centre, seemingly reinforces notions of centre-periphery relationships in the colonial visual economy. However, the widespread and horizontal dissemination of these images cannot be understated. The postcards represented on our interactive map represent only a small fraction of the kinds of images available. Although many of these images attest to the materiality of the postcard - they are faded, damaged, written over, and stamped - we cannot fully account for the journeys they have taken since their production. Where they did travel, though, we can speculate that these images helped to disseminate the idea of an imagined Algeria. For Edward Welch and Joseph McGonagle, the ubiquity of colonial photography in the production and circulation of postcards means that they are ‘not just symptomatic of colonial activity, but constitutive of it’ (2013: 14).

Two distinct genres of colonial images emerge through this production. On the one hand, cards portray the distinct landscapes and architectures of colonised territory, often segregating scenes of colonial modernity from depictions of colonised populations. On the other hand, cards recreated scenes of orientalist fantasy depicting the bodies, clothes, and habits of colonised peoples, fetishizing women in particular in overtly racialized and sexualized forms.

For the Cartography Of Exile we have focused specifically on cards which depict the space of colonial Algeria, its landscape and architecture, rather than reproduce the genre of images depicting colonised peoples. This is to allow a commentary to emerge on how the European settlers of Algeria forged imaginative connections with Algerian territory, especially when they recirculated these images in their own post-colonial collections of postcards and other images, as we shall explore in a later blog post.

However, in the next post in this series about postcards, we will first explore ways in which French and Algerian artists and writers have drawn on the latter category of colonial portraits as a form of resistance to the coloniser’s gaze, and the harmful racist and sexist hierarchies that they represent.