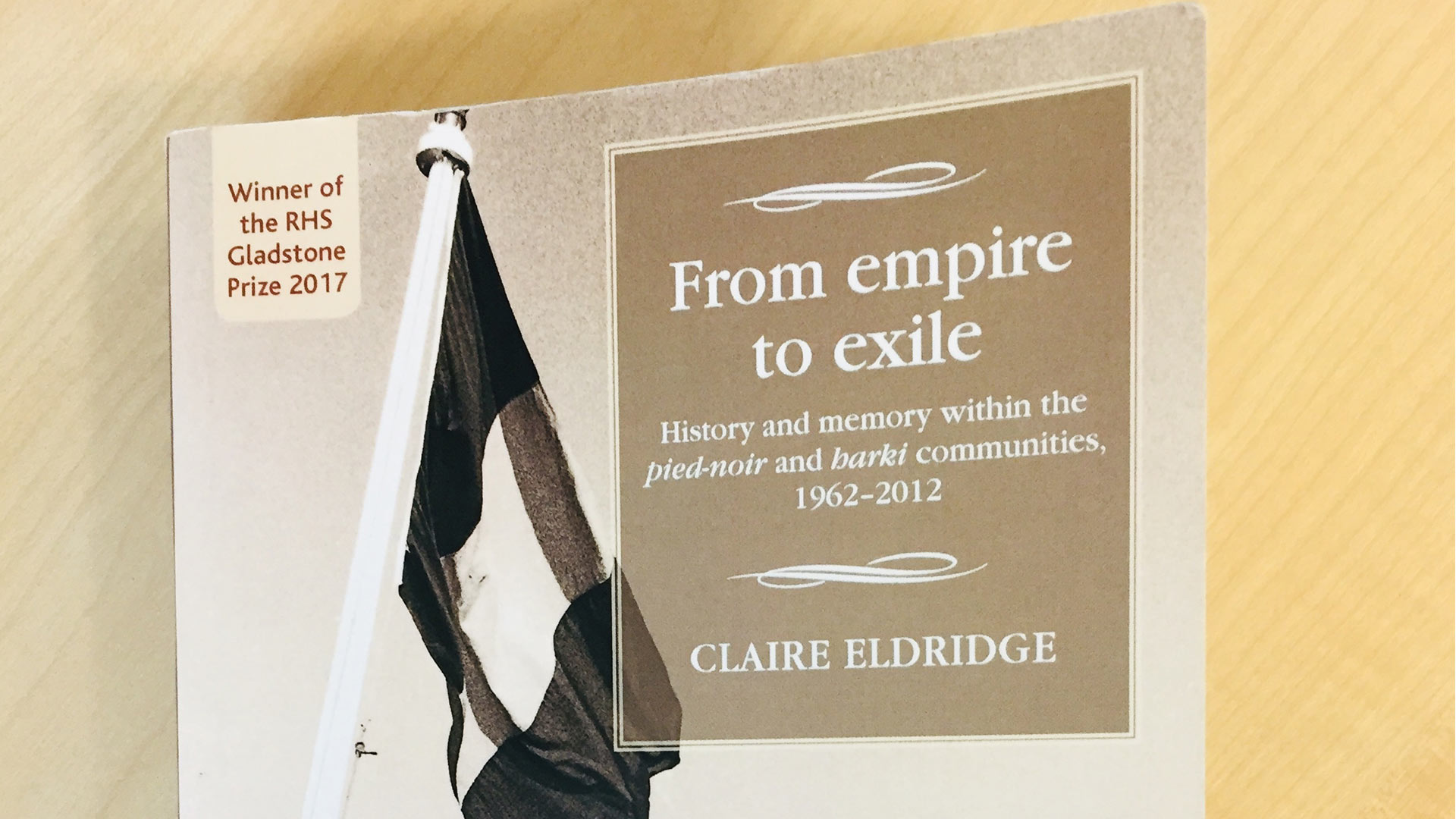

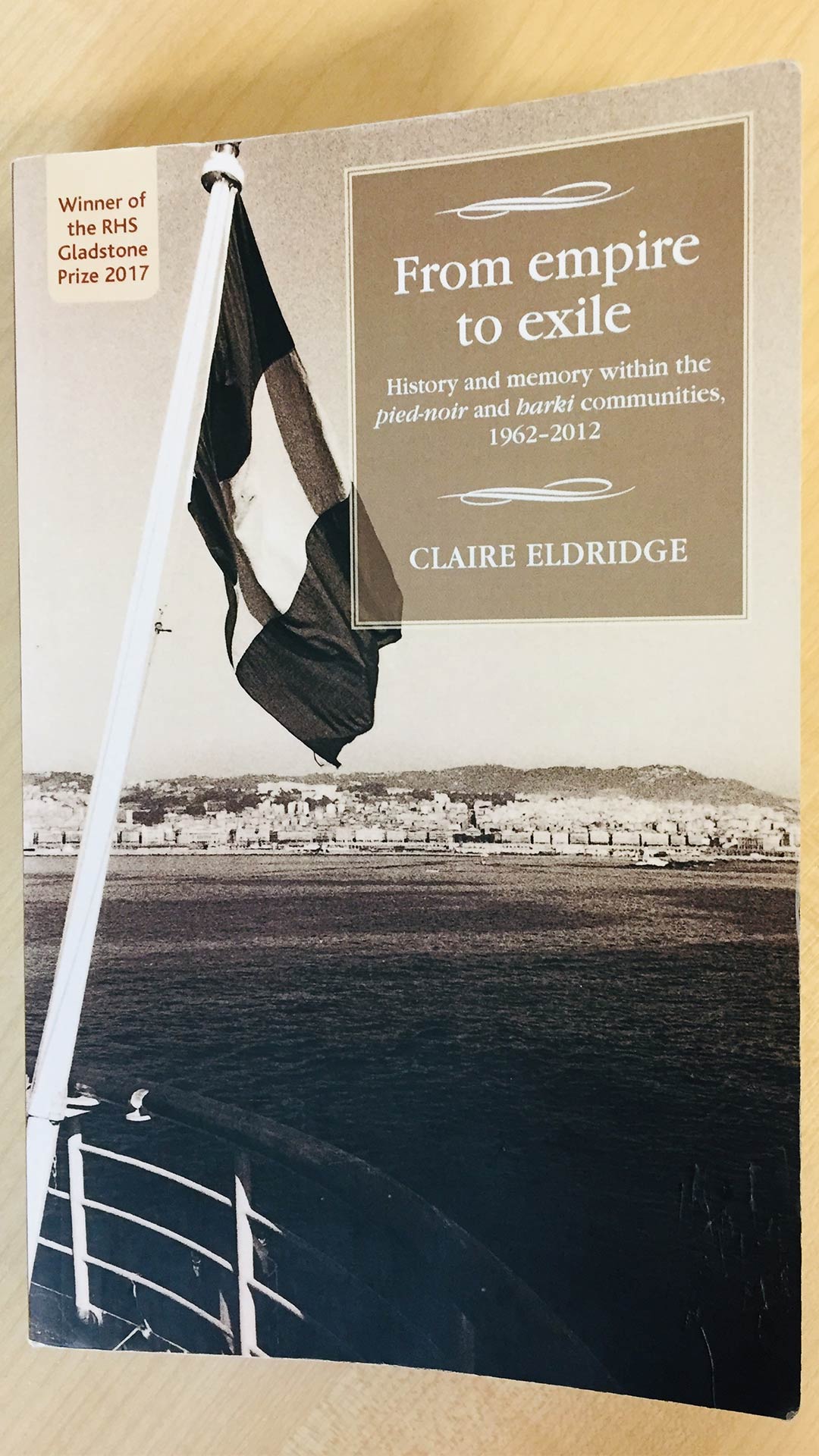

Dr Claire Eldridge on 'From Empire to Exile'

Published in 2016, Claire Eldridge’s important book From Empire to Exile: History and Memory within the pied-noir and harki communities 1961-2012 explores the commemorative afterlives of the Algerian War of Independence. In particular, she focuses on the practices and impact of pied-noir and harki activism on the commemoration of the Algerian War in France over a 50-year period, from 1962 to 2012. Claire kindly talked to Beatrice Ivey about her work on pied-noir activism, its future, and her current research on pied-noir soldiers during the First World War.

The book has two parts – the ‘The era of ‘Absence’ 1962-1991’ and then ‘The ‘Return’ of the War of Independence, 1991-2012’ – which addresses the dominant framework through which the memory of colonial Algeria has been narrated: in terms of long, amnesic repression and then a sudden memory boom. By pointing out the sustained and continued memory work of pied-noir activists, the book disrupts the notion of prolonged absence followed by over-abundance of memory in French-Algerian historiography. What memory frameworks have been important for you as you approach the memory activism of ‘pieds-noirs’ in France?

The theoretical models I used in my book were pretty conventional and centred on the idea of memory as socially framed, present-orientated, relational and driven by specific agents. Central to the book is the idea that memory is not an abstract entity floating somewhere in the cultural atmosphere, but rather something that takes shape within the societies it concerns, hence the value of tracking its historical evolution over time and across specific social, cultural and political contexts. Of course there’s the obligatory reference to Maurice Halbwachs and the cadres sociaux of memory. But at the same time I wanted to stress the role of particular agents in constructing and articulating memories.

Memory has no agency in its own right, as we know. It requires individuals to select, organise and articulate narratives, and it was these actors that I was primarily interested in. I found Jay Winter’s concept of ‘fictive kin’, which he borrows from anthropology, to be especially useful. ‘Fictive kin’ agents operate as part of civil society in the liminal space between the individual and the national, picking from the range of available individual memories those that are best suited to the creation and codification of a cohesive collective memory. Strategically chosen, these representations reflect an awareness of the need to organise the past so as to achieve certain objectives. The representations that are selected are not static, however, but subject to contestation and negotiation, and can therefore shift depending on the wider contexts. It’s this process of agency-driven, interactive memory creation that I tried to capture in my book which is primarily about highlighting multiple ways in which specific groups and individuals developed and/or engaged with particular narratives about the past to construct communal identities and to negotiate a place for themselves and their histories with French society and culture. And how these strategies and narratives changed over time in response to evolving contexts and their interactions with other memory activists.

In focusing on ‘pieds-noirs’ associations, your book benefits from a bottom-up approach in its historicisation of postcolonial memory. Why is this particularly helpful for your study and, perhaps, important for the study of colonial legacies in general?

During my research, and certainly by the time I came to write the book, there was already a lot of published research tracking the development of top-down or state-centric postcolonial memories and/or the absence of these. The literature on the experiences and activities of the groups most directly impacted by the War of Independence was, however, patchier. I felt that emphasising the bottom-up perspective and doing so over a sustained period of time was a useful way of calling attention to the mobilisation that different communities had undertaken and highlighting the various types of agency they had been able to exercise, while also reflecting on the power dynamics that had shaped whose voices had and had not been heard at various moments.

This also allowed me to foreground what these different groups had to say about themselves and to think about the significance of what they chose to accentuate or omit, and how this compared to the narratives and perspectives of other groups. The state is clearly a very important actor in this process, and often the most visible one. But it is not the sole reference point. It is equally important to consider the relationships between the state and the various communities who have a stake in debates surrounding colonial legacies. No actor or community is operating in isolation and engaging with the interactions between these different bodies helps build up a more rounded historical picture.

Overall, the bottom-up approach allowed me to show a different picture of the evolution of memories to the dominant narrative and, in particular, to highlight the multiplicity of voices and narratives that were present during periods of supposed national ‘silence’. This is a useful process in general, but it has particular value when we are talking about groups or histories that have struggled for visibility and legitimacy, which is definitely something that applies to postcolonial ethnic minority populations in France but also in other countries.

The books frequently refers to the presence of ‘pieds-noirs’ and ‘harkis’ on the television on shows like ‘Cinq colonnes à la une’. Is there a strong relationship between ‘pied-noir’ and ‘harki’ activism and the media? From a methodological perspective, how important is television for a bottom-up historical study?

The media are a very powerful vector of transmission when it comes to disseminating particular interpretations of the past. They can have a significant impact on the general public in terms of what they do and don’t know about a historical era, but also, and perhaps more importantly, on their perception of historical actors. For example, virtually no images of the transportation of harkis from Algeria to France in 1962 were circulated in the press, in contrast the very extensive coverage – in both words and images – devoted to the movement of rapatriés. This, in conjunction with the French media then being denied access to the various harki camps during the 1960s, is a fundamental part of why this community and their history remained ‘forgotten’ for so long. But the media were then equally instrumental in fostering and sustaining the greater levels of visibility that the harkis have enjoyed since the late 1990s. All memory-carrying groups recognise the power and reach of the media, hence why they work so hard to try and secure coverage, and coverage that is favourable to them. Or, in the case of the pieds-noirs, when they can’t secure the kind of media representation they want, they create their own media, including producing their own television series and documentaries.

Groups like the pieds-noirs and harkis thus actively engage with the media, which makes it a good space in which to look for evidence of the ways in which these groups try to exert agency. For example, when you watch pied-noir or harki spokespeople on television participating in discussion panels, news segments or documentaries, you get a clear sense of the message they are seeking to disseminate about themselves and how the seek to contest what they regard as inaccurate representations of their history. You also get the chance to see how they interact with other memories and their representatives, including the various hierarchies and power dynamics at play in these exchanges. So, television is yet another forum we can use to access the kind of grassroots perspectives my study was interested in, while also thinking about the strategies of dissemination the individuals and groups who participate in these shows are pursuing.

In your introduction and conclusion, you offer comparative case studies of post-Independence migration, such as the Portuguese retornados of Mozambique or the Moluccans who fought for the Dutch and were brought to the Netherlands from Indonesia by the Dutch government. Why are these international comparisons significant?

Decolonisation was not just something experienced by France, it was a global phenomenon; and so too were the population movement produced by this major historical shift. International comparisons help us to see the broader patterns and processes at work, while also underlining what was unique about the experience of each of the countries involved. The various European powers were also watching their neighbours for tips on how (not) to handle these kinds of events and their after effects, creating a series of connections and exchanges that have yet to be explored in detail.

Indeed, in terms of future directions for scholarship, there is a now sizeable body of scholars who are doing really exciting work on migrations of decolonisation and their legacies in specific countries such as Christoph Kalter (Portugal), Jordanna Bailkin (Italy), Wim Manuhutu (the Netherlands), Becky Taylor and Pippa Virdee (Britain), not to mention people working in non-European contexts. The quality of this scholarship is reflected in the number of excellent edited collections that bring together various case studies, not least Andrea Smith’s Europe’s Invisible Migrants, as well as monograph projects like Elizabeth Buettner’s Europe After Empire. Yet although these works range widely, they still tend to stick to a structure of one national case study per chapter. The next step is to write a history of migrations of decolonisation that transcends national boundaries while still being sensitive to the specificities of each country’s experience. This would definitely be a challenging project, for all sorts of reasons, but I think we have reached the point where there is enough historical knowledge about a sufficiently broad set of case studies for it to be possible.

Your book demonstrates, on the one hand, the wide range of ‘pieds-noirs’ and ‘harkis’ associations and, on the other, how ‘pied-noir’ or ‘harki’ identity can be homogenised by the very same associations. For example, the community as a whole has largely been associated with the political right and colonial apologists. What affect have these major associations had on anti-colonial and anti-racist activity in France?

There have been multiple impacts. On the one hand, the speed and strength of the initial mobilisation undertaken by pied-noir associations and their success in disseminating a vision of empire as a positive enterprise made them a force that anti-colonial and anti-racist groups had to contend with in order to get their own, quite different, messages about empire and its legacies across, even if this engagement was not always framed as an overt response to the pieds-noirs.

But it is important not to overlook the connections between some sections of the pied-noir and harki communities and anti-colonial / anti-racist activism. My book, for example, talks about the attempts to build bridges between children of harkis and descendants of Algerian migrants in France at specific moments such the 1983 March for Equality and Against Racism, or around particular commemorations like the 17 October 1961. Even if these attempts were complicated and not always successful, there is a history of shared ground in terms of personal experience and activism that merits highlighting. And I think the further we get from 1962, the more this connectedness and commonality has increased, as has been documented by scholars such as Giulia Fabbiano and Rosella Spina.

Are there other associations that differ from this right-wing model? How visible is their work compared to ANFANOMA and the Cercle algériantiste, for example?

Yes, absolutely. It is important not to take the dominant national groups, or the groups that get the most attention nationally as representative. There are various shades of pied-noir opinion and always have been. For example, you had Coup de Soleil, which was founded in 1984 and which under the leadership of Georges Morin sought to build bridges between the various communities that had comprised French Algeria by emphasising a sense of fraternity born of common geographical and cultural roots. Linking to your previous question, the initial impetus behind Coup de Soleil was a desire to participate in the anti-racist struggle, although the group’s agenda soon evolved into a broader set of aims.

You also have more recent manifestations of the diversity of opinion within the pied-noir community such as the Association nationale des pieds-noirs progressistes et leurs amis (ANPNPA). Founded in Perpignan in 2008 by the pied-noir Jacky Malléa, the association explicitly contests the right-wing ‘nostalgic’ depiction of empire that has a particularly strong support base in that town. It is fair to say that such groups have been less visible. But they have still been significant – Georges Morin was a well-known political activist with close ties to the Parti Socilaist, and Coup de Soleil had some very prominent associates members such as Benjamin Stora and Leïla Sebbar.

President Macron’s pre and post-election remarks vis-à-vis Algeria have caused significant outrage among ‘pieds-noirs’ activists, even provoking an apology after the Cercle algérianiste complained of his ‘crimes against humanity’ comments. Does this suggest that pied-noir memory is still active today?

I think the Macron ‘crimes against humanity’ episode demonstrated first that the pied-noir community remains active, although definitely with dwindling numbers, and can mobilise vocally around particular issues. And second, that they can still exert influence as shown by the ‘apology’ Macron felt compelled to issue afterwards. They are not as influential as they were in the 1980s and 1990s, but they can’t be entirely discounted, or certainly not by vote-seeking politicians.

Can this activism survive the transition to a third or fourth generation? How successfully have memory activist responded to the advent of the internet since the 1990s and social media since the late 2000s?

This is the real question. I think in order to continue, the nature of the activism needs to evolve in line with the priorities of younger generations – if they don’t feel that associations, the memories they carry and the causes they champion resonate, then they won’t participate. This evolution has been happening to varying extents in the pied-noir and harki communities for several decades now. Indeed, the use of the internet and social media are good bell weathers for the ways in which activism and activist agendas are changing. Some of the older associations, particularly on the pied-noir side, have been slow to embrace technological advances, as is quite evident from their web presence, or lack thereof. But as research by people like you and Laura Sims has shown, there are some really interesting and quite diverse forms of memory activism unfolding online. In some cases these are linked to more traditional forms of associational activism, but in other cases they are strikingly different. My study stopped in 2012, which is already a frightening number of years ago! So I am not the best person to answer this. But I will definitely be watching to see what you and the growing number of people working on postcolonial memories and memory activism find in the course of your research.

What are you working on now?

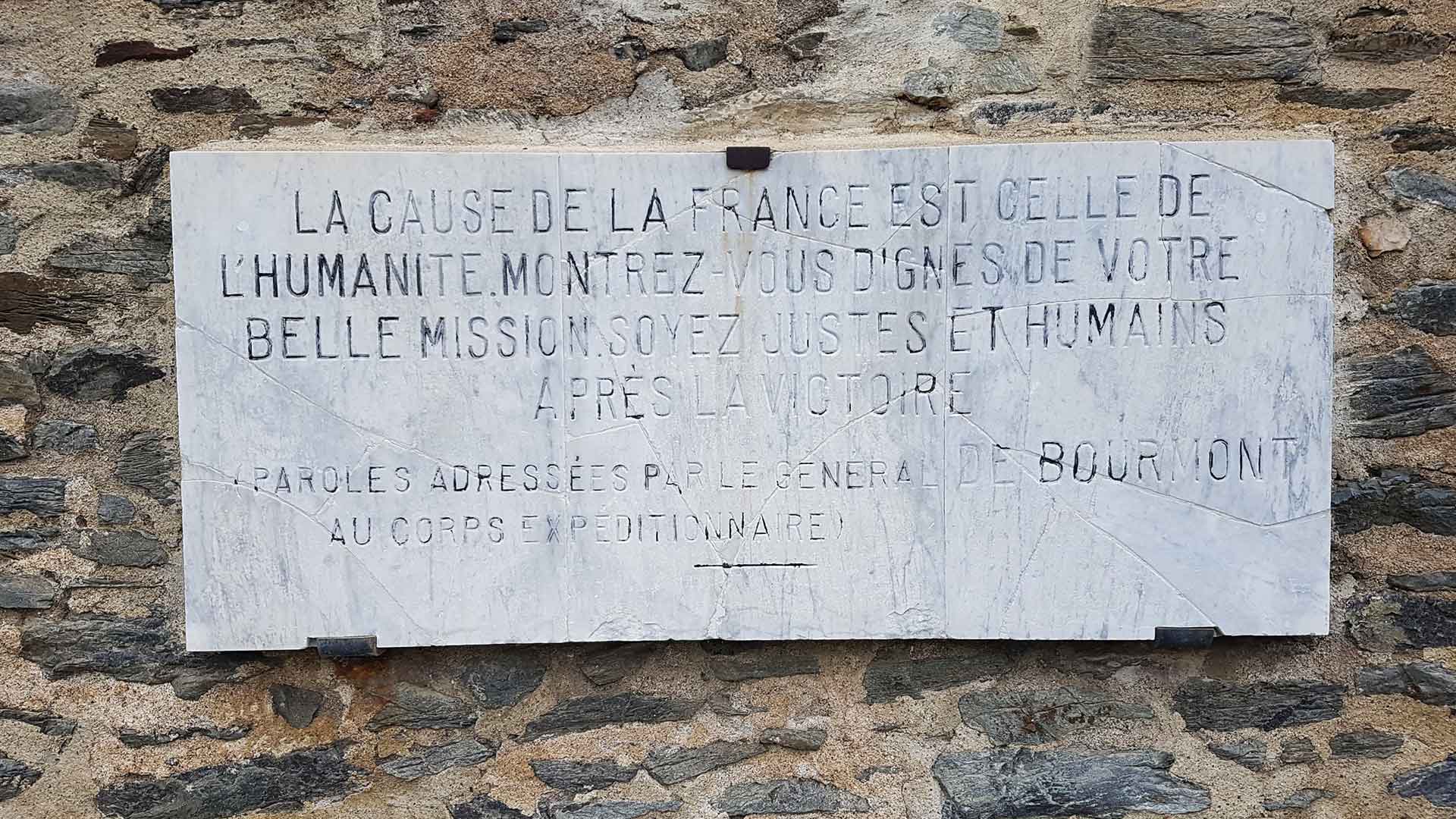

I’m still thinking about the settler community but I’ve moved back in time a bit. My current project looks at soldiers mobilised during the First World War from North Africa, both European settlers and indigenous colonial subjects. I’m interested in ‘crimes’ that these men committed while serving in the army and what these might be able to tell us about their experiences of the conflict and their interactions/relationship with each other and with the metropolitan French troops they served alongside.