From Algiers to Neuilly: The Duc d'Orléans Statue

This week it was announced that the mayor of Bordeaux, Alain Juppé, had stayed a decision to name a street in the Ginko, Bordeaux after Martinican psychiatrist, philosopher, and anti-colonialist Frantz Fanon. Citing ‘des incompréhensions, des polémiques, des oppositions que je peux comprendre’ Juppé’s move to block the naming has largely been blamed on far-right pressure, stemming from objections to Fanon’s anti-colonialist work for the FLN during the Algerian Revolution.

This effort to prevent the entry of Fanon’s name into the psycho-geographic space of Bordeaux points to anxiety surrounding the visibility of colonial legacies in French towns and cities. Jennifer Sessions, Associate Professor of History at the University of Virginia, notes that there have also been attempts to call into question the unchallenged visibility of imperialist figures and perpetrators of slavery in statues and monuments throughout France. Campaigns have been launched to decolonise public space, modeled along similar lines to the international campaign #RhodesMustFall, adopting slogans and hashtags like #FaidherbeDoitTomber in Lille and #DéboulonnonsBugeaud in Orléans. However, these have failed to gain widespread traction. As Sessions puts it: ‘France has been surprisingly absent from this global movement’.

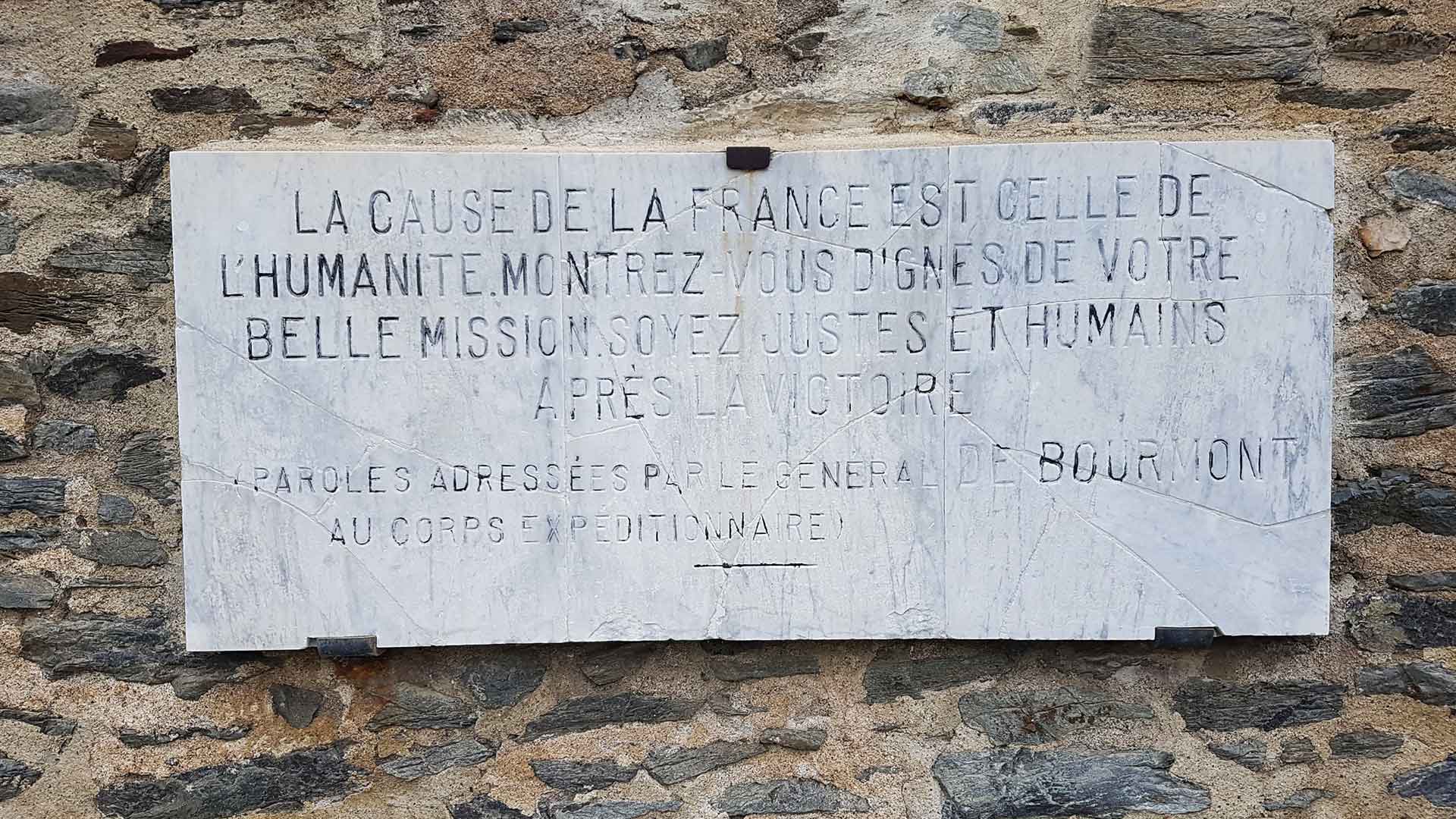

Sessions suggests that these campaigns illustrate the difficulty of identifying imperial monuments in the first place. Not because they don't exist, but because there are so many and simply blend into the décor of French public space. She was kind enough to talk to the ‘French Settlers’ project about her work on one example: the equestrian the Duc d’Orléans statue in Neuilly which, at first glance, exhibits no sign of its colonial symbolism:

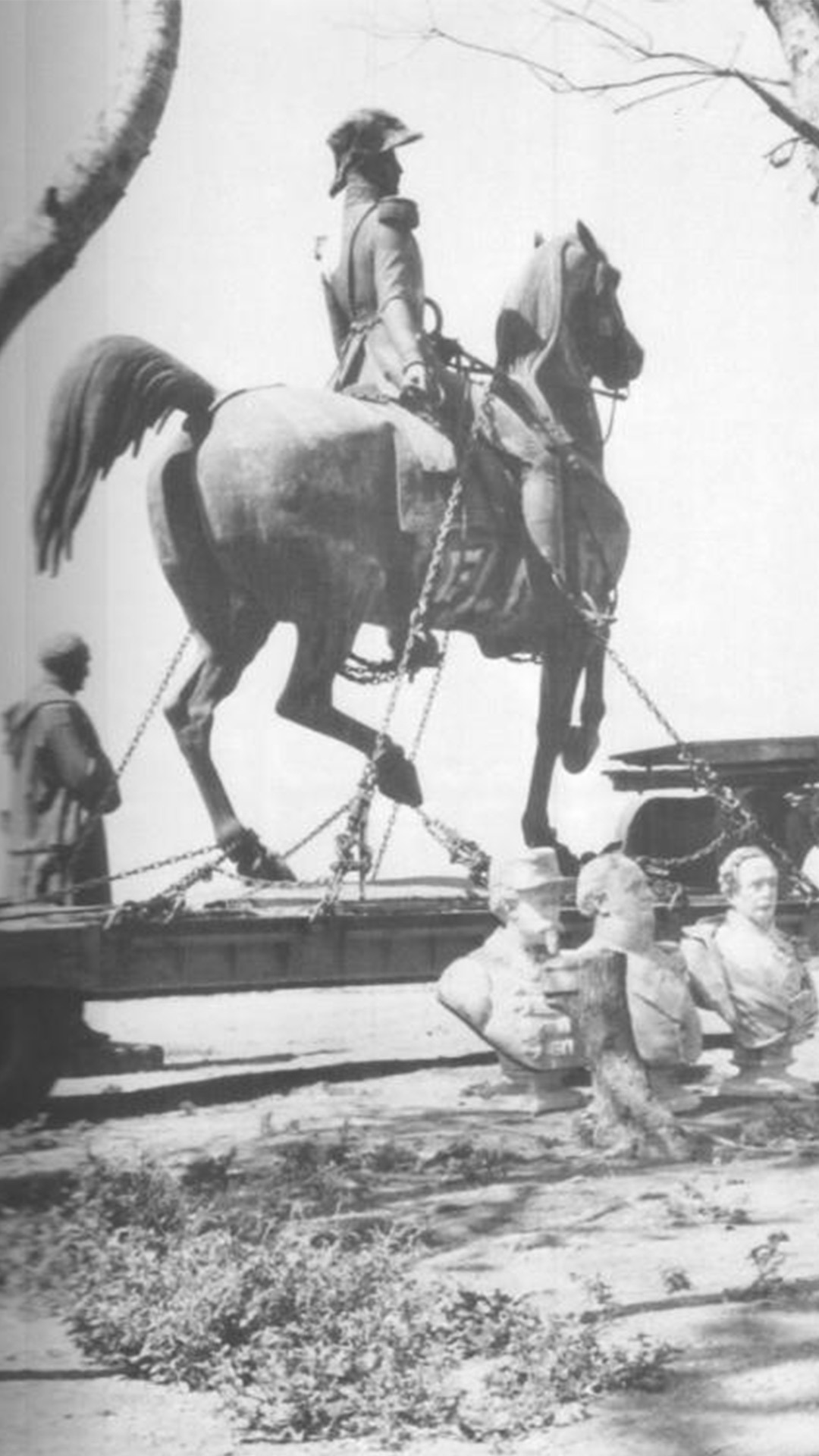

Cast in bronze from cannons captured from Constantine and Algiers, the statue of Ferdinand d’Orléans stood against the Djemaa el-Djedid mosque (Mosquée de la Pêcherie) in Algiers from 1845 until 1963 (then the Place du Gouvernement, now Place des Martyrs). The crown prince of France’s July Monarchy had contributed to the invasion of Algeria in 1835 and so, following his accidental death in 1842, sculptor Carlo Marochetti was commissioned to produce a monument to the prince and, by extension, the colonial conquest of French Algeria.

However, the statue can now be found on a roundabout surrounded by parked cars in the Parisian suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine (Place du Duc d’Orléans). How did the statue come to leave Algeria? Why did it find a new home in Neuilly-sur-Scène? What does the statue mean to ‘pieds-noirs’?

Surprisingly, the project to resurrect the statue in Neuilly did not start with ‘pied-noir’ cultural associations, like in the case of some of the other monuments covered in the blog. Instead, royalist groups saw this as an opportunity to reconnect Neuilly with the July Monarchy: the Duc had died in Neuilly, where the Orléans family had one of its estates. Indeed, their motivation to rearticulate such ties in public space is clear when we note that the Marochetti was among the first 25 statues from Algeria to be reclaimed by Metropolitan entitled (out of a total 150 colonial monuments that were repatriated following independence in 1962) (Session 2017: 196).

In her work on the statue’s unusual trajectory from prominent Algiers landmark to a Paris suburb, Sessions notes that Marochetti’s monument is a pertinent symbol of French colonial memory due to its very ambiguity:

Its historical and symbolic connections to the colonial context are not immediately visible in its material form, which is the case with many French colonial monuments. In many instances, because statues, in particular, took the form of fairly generic “grands hommes,” their colonial ties and meanings are not evident unless you know the specific biography of the individual depicted or the specific history of the monument itself.

Behind the generic ‘grand homme’ of the Marochetti statue, then, what are the diverse (and perhaps competing) historical narratives? To what history does the Duc d’Orléans belong? To the 1830 conquest of Algeria? To the July Monarchy? Or to the ‘pieds-noirs’?

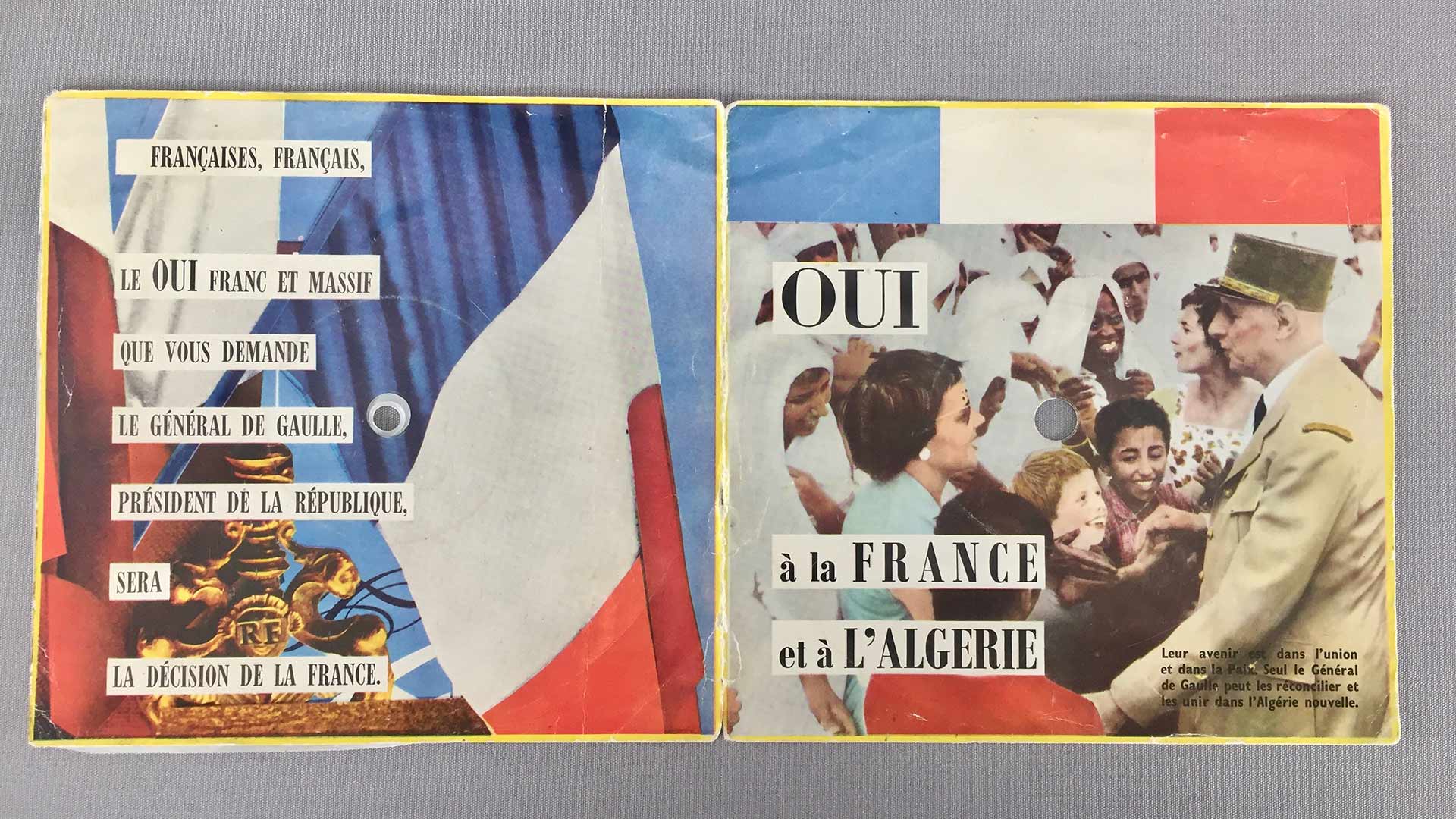

By the time the Marochetti statue had been inaugurated in Neuilly (38 years ago today) on 13 February 1981, royalists groups had spent many years negotiating with competing plans for the statue to be re-erected in Toulon on 14 June (the anniversary of the French invasion of Algeria). Neuilléen officials had become increasingly aware of the controversies over the statue as a symbol of France’s colonial past and sought ways to mitigate potential scandals. Therefore, as Sessions shows, the political work leading up to the statue’s inauguration is an excellent example of the ‘important shifts in the relationship between the local and the national in postwar France’, reflecting the ‘the entanglement of commemorations of French Algeria with other political and cultural processes’ (Sessions 2017: 195).

Sessions notes that pieds-noirs attendees to the inaugurate felt marginalised during the ceremony on the cold February morning. Although a military band played Sidi Brahim alongside the Marseillaise, and despite the invitation of repatriate leaders and the respected Si Hamza Boubakeur of the Paris Mosque, pieds-noirs felt that their suffering in France and ‘contributions’ to French Algeria had not been sufficiently addressed.

Indeed, Sessions contextualises this ill-feeling in Neuilly within a period of rising tensions around the commemoration of French Algeria. Only the previous year, in June 1980, the Toulon monument to the ‘martyrs of French Algeria’ supported by the pro-colonialist OAS had been bombed a week before its inauguration.

On the one hand, the ostensible innocuity of the ‘grand-homme’ Marochetti statue has meant that, in some ways, Neuilly was able to avoid such violent controversies. On the other, pieds-noirs associations linked with the statue feel that their interests have been lost in the ‘entangled politics' commemorations that underpin its ambiguity as a symbol of French Algeria. Fading into the grey of the Parisian suburb, the pieds-noirs who visit the former Algiers landmark (in person or virtually via Street View) are reminded once again of the impossibility of returning to a lost time and place.