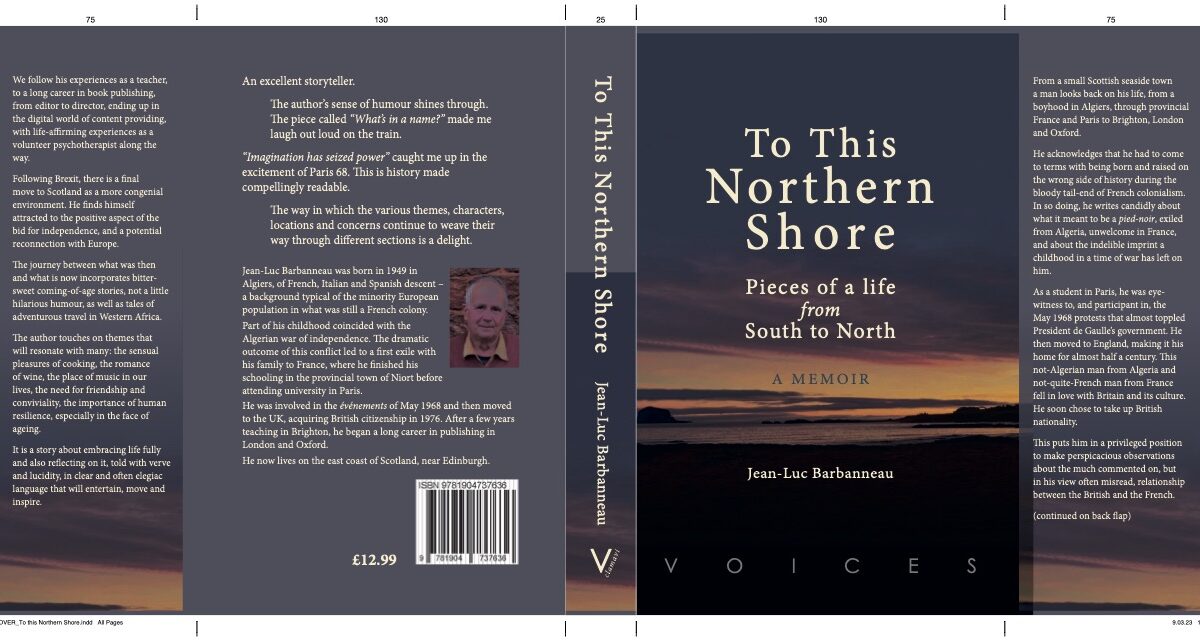

A new publication by Jean-Luc Barbanneau recounts a life that moves from French Algeria, via the Paris of May '68, to Scotland.

Jean-Luc Barbanneau was born in 1949 in Algiers to a family of French, Italian and Spanish origins. He lived his childhood amidst the violence of the Algerian War, and fled with his family to France in the exodus of 1962. His new memoir recounts his experiences of struggling to integrate into a provincial school, before moving to Paris in time to participate in the events of May '68. Thereafter he moved to Britain and a career in publishing before a final move to the northern shores of the east coast of Scotland.

Memoirs by exiled pieds-noirs are not a rarity: mailing lists in France continue to be full of new publications, while the more literary among them jostle for space on the packed shelves of bookshops. Memoirs written in English are less common, unsurprisingly. One of the delights of this project has been the opportunity to meet people of European descent born in Algeria, and their children, whose trajectories have brought them north to settle in Scotland. While I have been fortunate enough to hear many of their stories in person, fewer make their way into print.

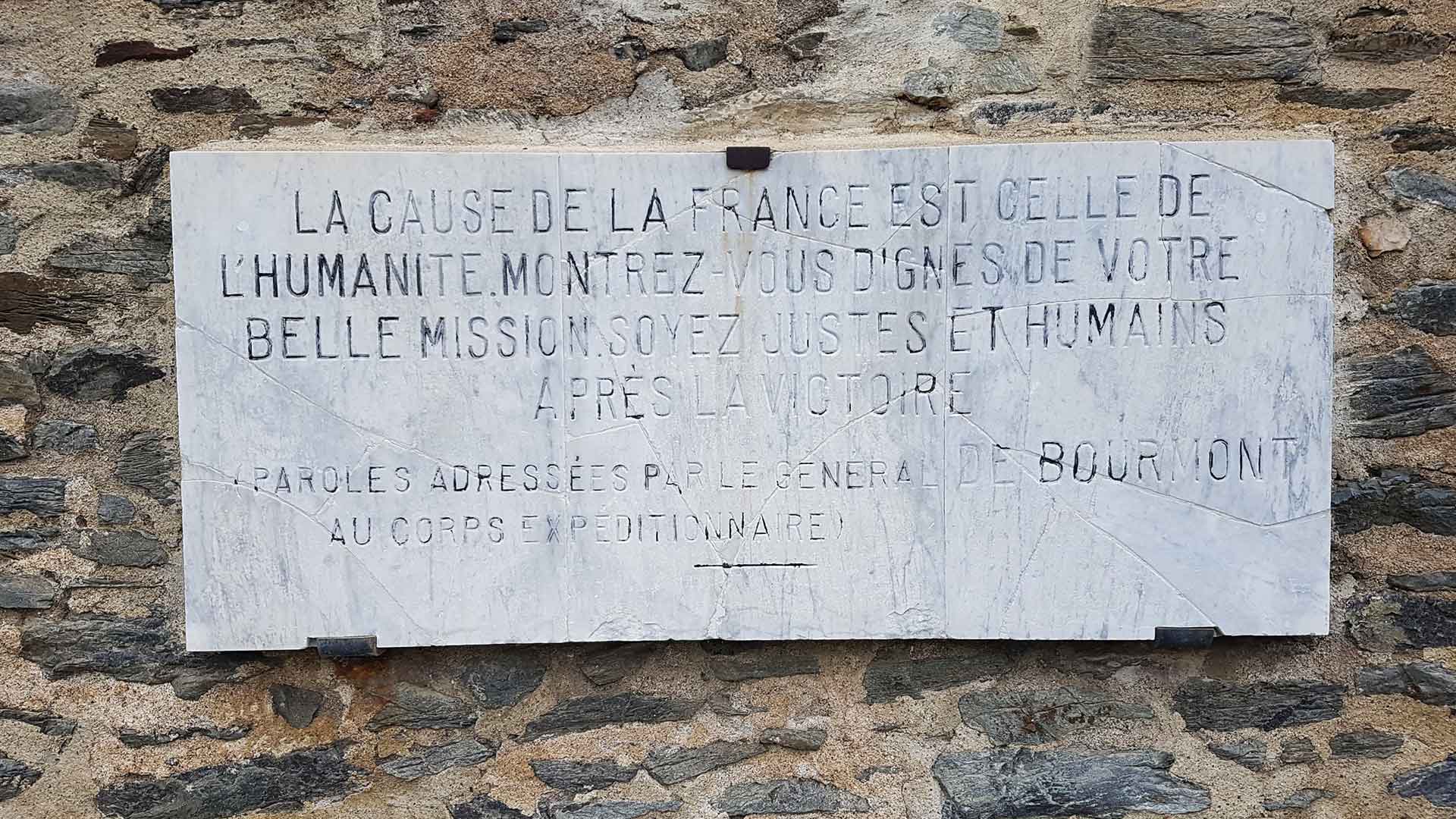

One exception is the story of Jean-Luc Barbanneau, a pied-noir who became an established figure in the world of publishing, and who now has authored an account of his own experiences. It's a fascinating read. The familiar descriptions of settler life in French Algeria appear, but marked with an urgency that comes from the perspective of a child growing up surrounded by the violence of war, including the massacre of the rue d'Isly in March 1962. Barbanneau is careful, though, to frame his childhood memories with the political perspectives of the adult: among pied-noir narratives his account stands out as being unusually clear-sighted on the evils of colonialism, and the responsibilities of those who lived within the colonial system. His position echoes that of Marie Cardinal and her comments on her pied-noir family, but is accentuated by the reflective space created by time and geographical distance.

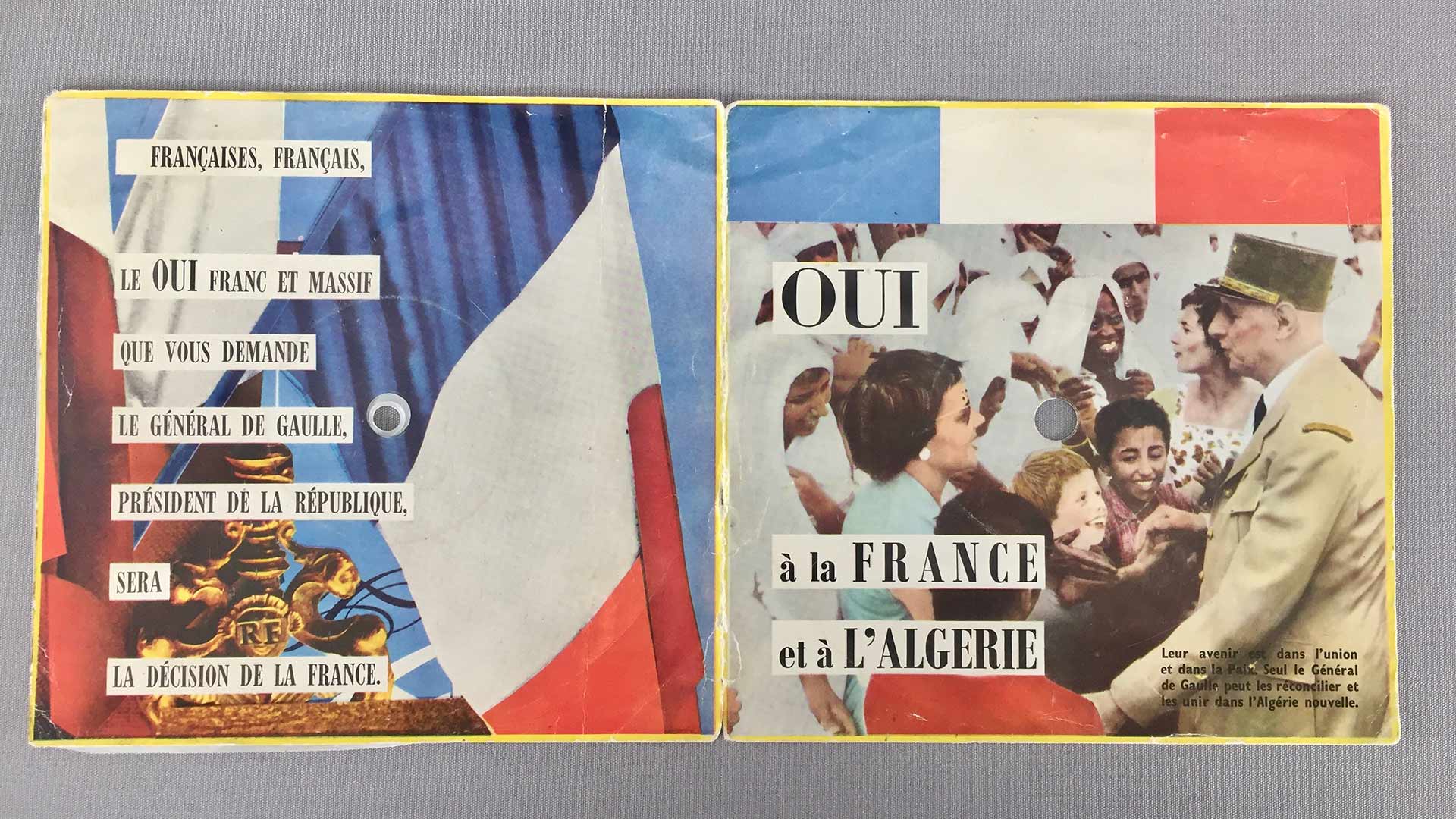

Barbanneau's move to France highlights the often-reported hostility which greeted repatriates from Algeria, but as he makes clear, the coldness extended beyond the schoolyard to members of his own family. It comes as a reminder of the divisions that striated French society in the 1960s, divisions evidence in the coincidence that brought him to Paris shortly before the events of May '68 placed him at the site of the second of France's great post-war upheavals. Again, the eye-witness account lends an immediacy to the narratives of history books.

The sense of dislocation that accompanied many pieds-noirs, who struggled to reconcile their French citizenship with the cultural differences that they faced on arrival in France meant that Barbanneau's time in France was short-lived, with a further move to England proving to be permanent. His account of the social differences between France and Britain in the 1960s adds depth and context to the shift from Algeria to France that he had already experienced. Certainly it provided him with the opportunities to begin a career in publishing that lasted for several decades until retirement and, latterly, the referendum on membership of the EU, led him to a final exile north to the shores of the North Sea and a new home in North Berwick. While not all readers will be convinced by his descriptions and appreciation of Scottish warmth and welcome, the reflections on the move from the shores of the Mediterranean to those of East Lothian provides a fitting frame for a moving account of a life lived through some of the major upheavals of post-war France.