Postcards III: Nostalgérie

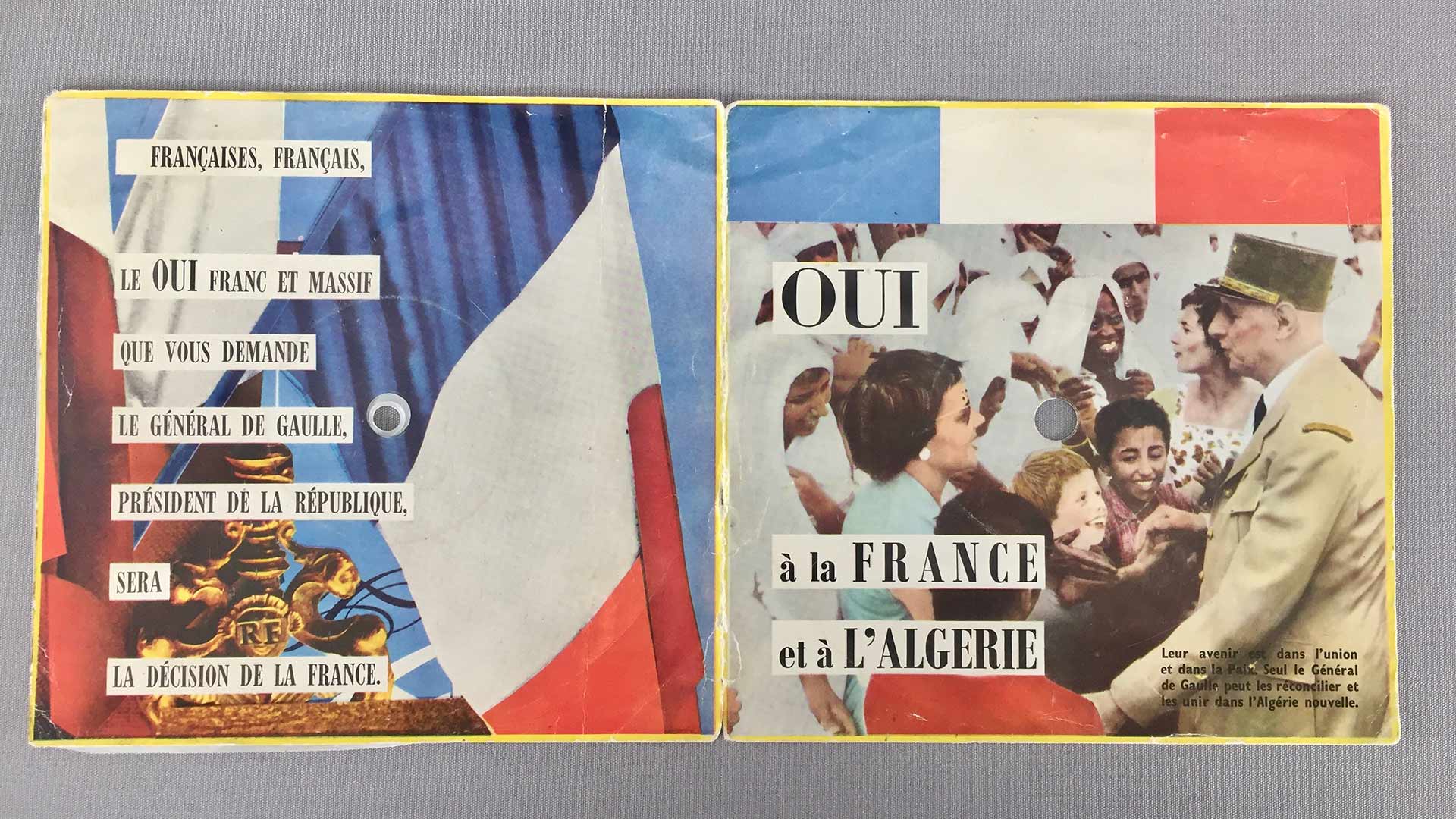

Pathologised as an overly romanticised sense of a paradis perdu in Algeria, pied-noir nostalgérie and colonial postcards seem to go hand in hand.

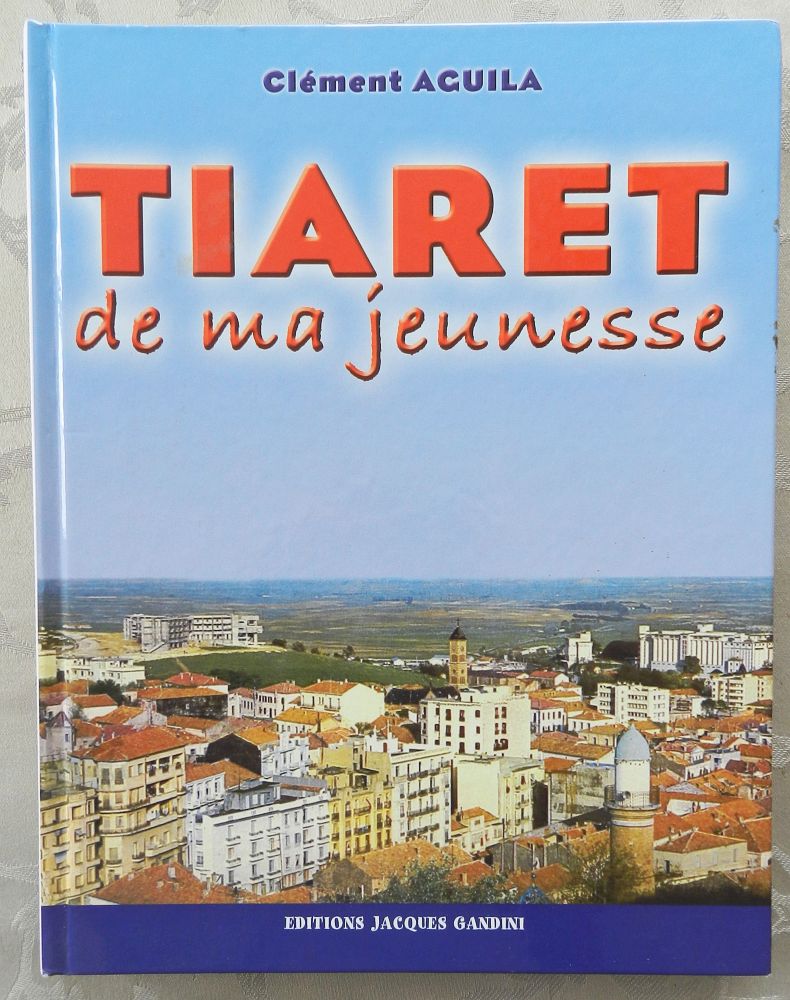

A number of these postcards are collected and reproduced in various phototexts published by members of the pied-noir community in France. In these publications, postcards are framed as an authoritative depictions of what Alger, Tiaret, or Tlemcen would have looked during their childhoods or the lifetimes of their ancestors. The idea that they were products of a booming early 20th century industry financed by the French state for tourists and travellers is quite distant.

In this respect, the postcard is used a historical source, but its framing is deeply affected. The publications not only record a sense of lost connection with an Algerian homeland, but actively recreate this imagined homeland through text and image.

- Élisabeth Fechner (2005) Souvenirs de là-bas : Alger et l’Algérois

- Paul Azoulay (1980) La Nostalgérie française

- Taddy Alzieu (2005) Tlemcen et l’Ouest de l’Oranie

- Clément Aguila (2004) Tiaret de ma jeunesse

- Jacques Gandini (1995) Alger de ma jeunesse, 1950-1962

Mary Vogl (2003: 175) cites Paul Azoulay’s La Nostalgérie française (1980) as an example of an uncritical re-production of colonial-era postcards and, consequently, their racist connotations:

Azoulay is praised in the preface for reproducing these old postcards, which can supposedly help the reader understand an era that witnesses the existence of two separate societies, one privileged and the other exploited. The separation between the two societies is indeed evident in the book, but what is missing is an explanation of how and why this came to be. Instead, Azoulay offers only “the Memory I keep my ALGERIA”: sunshine and happy times of the French colonials.

In their analysis of Jacques Gandini’s Alger de ma jeunesse, 1950-1962 (1995), Teddy Alzieu’s Alger : mémoires en images (2000), and Élisabeth Fechner’s Souvenirs de là-bas : Alger et l’Algérois (2002), Edward Welch and Joseph McGonagle suggest that the recirculation of these postcards, among other visual artefacts, can do more than simply reproduce colonial-era racism, but also reinforce the historical agency of the pied-noir communities. They not only serve ‘as vehicles for nostalgia’, but also as a ‘disruptive reminder of France’s last major colony as a triumph of modernity and modernisation’ (2013: 38).

While Welch and McGonagle also critically assess pied-noir phototexts as being firmly within a narrative that confirms, rather than challenges, colonial perspectives, they do not dismiss nostalgérie or overlook its effect on collective and historical engagement with the European settlement in Algeria and their sense of dispossession since 1962 (2013: 17):

Nostalgia should be taken seriously as a mode of remembrance and historical understanding […] we need to get to grips with its forms of expressions, its politics and ethics. Such issues are all the more timely given […] both the persistent presence of images of French Algeria in the broader public sphere in France and its increasing visibility in French culture.

A digital nostalgia

In the course of editing and uploading around 175 digitised postcards to this project’s website, what struck me is the continued and profound resonance these images seem to have had for members of an online community of people seeking to piece together a visual archive of French Algeria.

There are countless websites, forums, youtube videos, and pinterest accounts that are dedicated to amassing and reproducing postcards of colonial Algeria.

Similar to the phototexts, a large proportion of images were taken in the early 20th century (like the ND or LL cards) but they have become flashpoints for internet users wanting to recall their childhoods during a much later period. Reflecting the demographic trends of pied-noir settlements in the late colonial period, most of the content refers to the street names and general topography of coastal urban centres such as Oran, Algiers, Bône.

For the interactive map, I wanted to see how closely I could match the subject of the image to its present day topography which I accessed through google maps. This was sometimes difficult, especially for smaller towns in the south. Very occasionally, a forum discussion would cite both the current and colonial street or place name – Square Post Saïd (ex Square Bresson) – but most of the time the postcards were uploaded without contextualization or with the original caption (in themselves unreliable). Frequently, while browsing these sites, I got the impression of a colonial idyll, frozen in the past, rather than a living space with layers of history that existed both before and after French colonialism.

Cartography of exile

Les paysages sont comme les livres : ils nous ouvrent à la vie mais leur sens change selon l’âge et les circonstances. Tel arbre du paysage, tel personnage de roman, qui nous paraissaient insignifiants au premier abord, deviendront majeurs et essentiels à la relecture. Et c’est là le charme des paysages. Comme nous ne leurs posons jamais les mêmes questions, ils ne nous donnent jamais les mêmes réponses. Ils vivent et changent avec nous. Et, matrice de notre mémoire, ils nous constituent à jamais.

Jean Pélégri 'Ma mère, L'Algérie'

For Jean Pélégri, born in Mitidja in 1920, returning to the landscape of his native Algeria is a way to reflect on the ever-fluctuating nature of memory. In visualising the past, he contemplates what comes into focus, what remains just outside the frame.

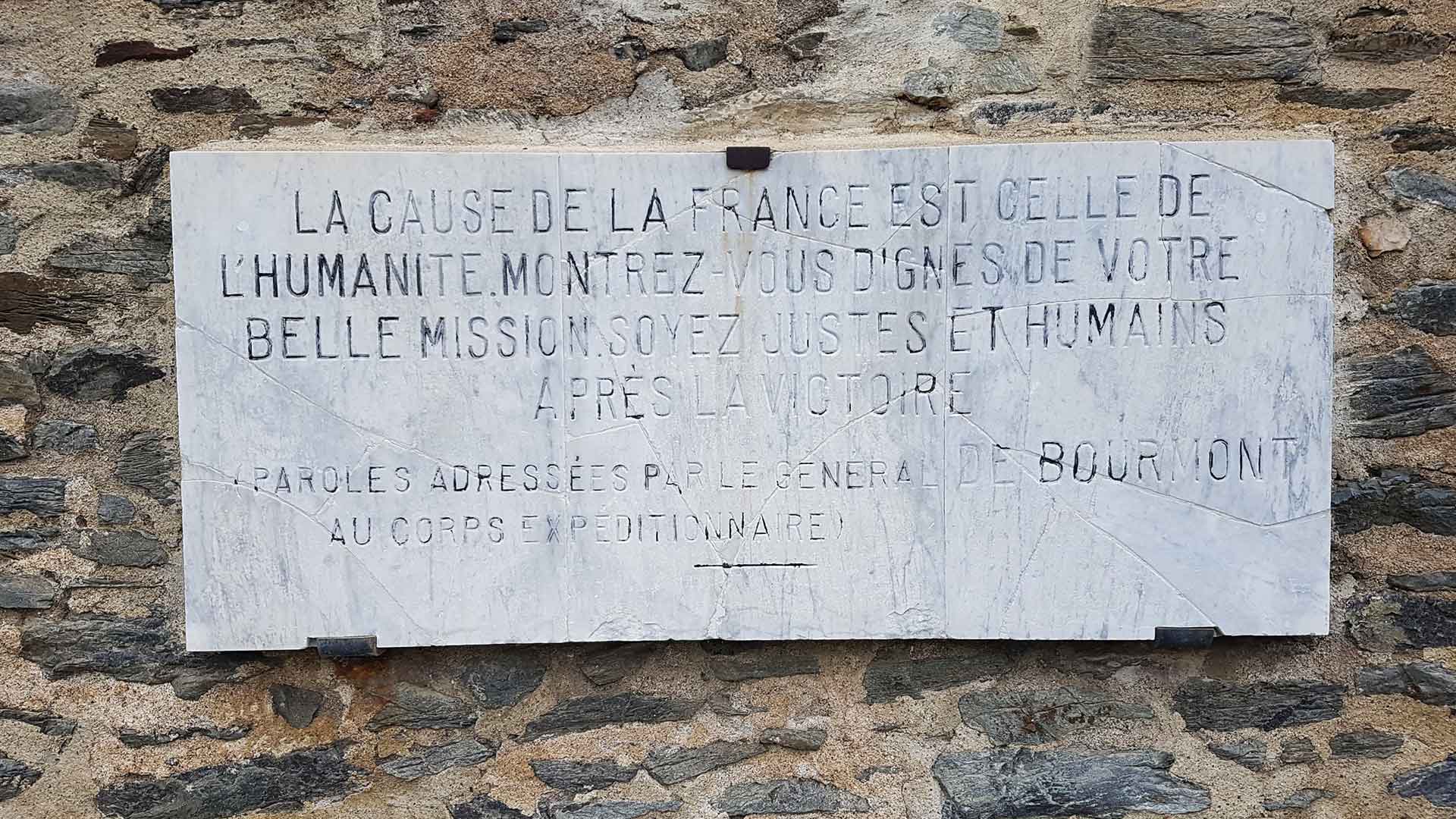

The Musée Sidi Ferruch in Port-Vendres near Perpignan originally collected the postcards that we are using in our project. Like the phototexts, their collection has very few images with figures in them. Most are landscapes, taken form tall buildings or natural vistas, designed to show the splendour of French architecture and the modernisation of colonial space.

For Musée Sidi Ferruch, the goal is to help pieds-noirs and other interested parties to reconstruct colonial Algeria in their imagination, to keep a memory alive. The spatial and architectural nature of the postcards in their collection is key to this. However, by marginalising figures of Algerians, of the colonised, it is easier to maintain an image of the triumph of French modernity in Algeria and romanticise its achievements.

As Welch and McGonagle put it, the spatial arrangements of these postcards help the collector to ‘elide the moment of departure in favour of images of accomplished modernity, and a recognisable sequence of locations which viewers can inhabit and invest with their own memories’ (2013: 45).

Therefore, in also reproducing these images online, this project must account for the ways we are participating in a tradition that has tended to uncritically reproduce colonial imaginaries and spatial hierarchies.

This project does not dismiss these postcards as vehicles of colonial nostalgia, nor claim to reinforce the narrative of colonial Algeria as a triumph of modernity. Instead, in situating the images geographically to the site of their original staging, we are highlighting the anachronistic connections between the colonial past and contemporary topography, signalling the (sometimes-surprising) continuities and ruptures.

By layering these images into a map, alongside critical commentary elsewhere in the website, we hope that it can remind us of the ways in which the French (idea of) colonial Algeria was always already an imaginary one. These colonial-era images are re-presented to a public audience but not as neutral depictions of an isolated past, frozen in time. Like Pélégri's landscape, these are artefacts that are undergoing a constant process of re-signification and can potentially shed some new light on the overcharged narratives concerning Algeria’s past.

References

Vogl, Mary (2003) Picturing the Maghreb: Literature, Photography, (Re)Presentation. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield.

Welch, Edward and McGonagle, Joseph (2012) Contesting Views: The Visual Economy of France and Algeria. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

The postcards are reproduced with the kind permission of 'La Mer à Boire’ society and the Redoute Béar Museum in Port-Vendres.

Les cartes postales sont reproduites avec l’aimable autorisation de l’association 'La Mer à Boire’ et le musée à la Redoute Béar à Port-Vendres.